PART I

RESPONDING TO CHANGE

WorldFish 2030 Research And Innovation Strategy

DownloadOUR BLUE PLANET

IS CHANGING

In recent years, a global call to action has emerged for a food systems transformation to healthier and sustainable diets. Public and private sector actors have joined forces to argue that the full realization of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development will only be possible if we change the current ways of producing, distributing and consuming food to sustain health and well-being for people and our planet, now and in the future.

Scientists have been warning for decades that increasing temperatures, extreme weather events and dramatic shifts in ecosystems can unleash a range of public health problems. These problems are global and wide-ranging: infectious diseases caused by microorganisms and carried by insects; water- and foodborne diseases from floods; airborne pathogens resulting from droughts; and air pollution or increasing contact between wildlife, farmed animals and humans. The case could not have been made clearer by the massive wildfires that engulfed the world’s largest tropical wetlands in the Amazon rainforest or the locust plague in East Africa in 2020. And then came the COVID-19 pandemic, which brought the world to a standstill and left us scrambling for innovative solutions. It has become the public health emergency that is testing (perhaps like no other event before it) our collective capacity to respond effectively to large-scale existential threats. It has altered the way we live and the way we think about our relationship with nature.

Growing inequality has become an instrument of political populism, exclusion and xenophobia. At the same time, the #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter movements are giving voice to women and men across the world to denounce the ubiquity of gender and racial violence and discrimination. Young activists like Greta Thunberg have become poster children for unprecedented social mobilization on climate change. Many individuals, companies, organizations, cities and countries have started to take extraordinary actions to become green and reduce their carbon footprint.

Our world as we know it—the physical, the digital and the biological—is constantly being shaped by new trends, threats and opportunities, affecting all disciplines, communities, industries and governments. They are changing the way we live and work, and even challenging the very idea of what it means to be human. In a complex, fast-changing world of ongoing shifts in ecosystems, politics, markets, social and cultural norms, and technology and digital transformation, making the right choices can be a daunting task. In the age of “fake news” and “alternative facts,” the COVID-19 emergency is there to remind us that good choices must be informed by solid scientific evidence and innovations. Disruptive technologies in the private and public sectors have been giving rise to unprecedented innovation and new ways of doing business through public-private partnerships. These technologies co-create shared value for the benefit of both business and society, while sustaining our natural resources within the boundaries of our precious blue planet.

A rising tide of companies, nonprofits, social entrepreneurs, international organizations and civil society actors is eager to tap into the considerable potential of the “blue economy” or the “ocean economy.” The hope is to generate clean and inclusive growth, new and better jobs, and unparalleled innovation to meet the global goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. More than ever, bold policy and investment decisions are needed to enable an effective food systems transformation toward healthier and sustainable diets and to make changes in governance frameworks for shared prosperity and sustainable management of scarce resources. They are also needed to make shifts in consumer behavior and choices and in good business practices with positive impacts on communities and the environment.

The 2030 WorldFish Research and Innovation Strategy: Aquatic Foods for Healthy People and Planet reflects our commitment to do our part in making bold decisions possible. It is through science that we will help to illuminate sound paths toward a sustainable food systems transformation with aquatic foods and to meet the goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in all three of its dimensions—social, economic and environmental.

OUR VISION, MISSION AND

RESEARCH WORK

Our vision

An inclusive world of healthy, well-nourished people and a sustainable blue planet, now and in the future.

Our mission

To end hunger and advance the SGDs by 2030 through science and innovation to transform food, land and water systems with aquatic foods for healthier people and planet.

WorldFish is a nonprofit research and innovation institution that creates, advances and translates scientific research on aquatic food systems into scalable solutions with transformational impact on human well-being and the environment. We are part of One CGIAR, the world’s largest agricultural innovation network, whose mission is to “end hunger by 2030 through science to transform food, land and water systems under threat of climate change.” Within One CGIAR and the wider global agricultural research agenda, we have a unique research mandate that focuses on the role and contributions of aquatic food systems to the 2030 SDGs

Our mission is focused on SDG 2: Zero Hunger but pays special attention to SDG 14: Life Below Water, and we leverage both of these goals to score progress on other multiple SDGs. Our work explores the potential of aquatic food systems as an important source of food and their role in the global transformation of food systems toward healthier and sustainable diets in the face of climate change.

Globally, aquaculture is the world’s fastest growing food production sector, and fish and aquatic foods are the most traded food commodity. Our work plays a critical role in realizing their potential for sustainable development in low- and middle-income economies. Our research on the value of small-scale fisheries to social, environmental, economic and governance contributions at local, regional and global scales supports the efforts of national governments to implement SDG 14: Life Below Water.

We believe research on aquatic food systems is critical to meeting shared global aspirations for establishing inclusive, efficient, sustainable, nutritious and healthy food systems capable of achieving the SDGs by 2030. However, research alone cannot provide people with more and better food, improve environmental sustainability or reduce climate risk. We recognize that transformative change requires our work to be situated within an innovation ecosystem of partners, stakeholders, networks, assets and institutions to turn research into demand-driven products, services and solutions at scale. This is critical to accelerating the speed of innovation in food, land and water systems to meet the increasing challenges of climate change, hunger, malnutrition, poverty, social inequality and environmental degradation.

Success in our world depends on ensuring research is relevant, credible, legitimate, and effective (ISDC 2020), as well as open and accessible to everyone. It is research like this that will guide, inspire and build knowledge, know-how and capacities for innovation and transformative action from public and private sector actors and institutions at all levels of the food system. Across disciplines and sectors, our approach to research and innovation connects and empowers women, men and young people for change for the long term. Research excellence and engagement with national and international partners are at the heart of our efforts to set new agendas, build capacities and support better decision-making to drive sustainable development in low- and middle-income countries in Asia, Africa and the Pacific.

Our research and innovation work spans climate change, food security and nutrition, sustainable fisheries and aquaculture, the blue economy and ocean governance, OneHealth, genetics and AgriTech, and it integrates evidence and perspectives on gender, youth and social inclusion. We work with government agencies, fishers, aquatic food producers, processors and consumers, community representatives, advanced research institutes and extension agents, civil society groups, businesses and social entrepreneurs. It is through our close collaboration and dialogue with our partners that we can accelerate the process of putting aquatic food systems on a low emissions pathway and enhance the adaptive capacities of the people, institutions and industries that depend on them. Our ultimate goal is to ensure sustainable and resilient food systems that deliver more diverse, healthy, sufficient and affordable diets with aquatic foods, and to improve livelihoods and greater social equality, within planetary and regional environmental boundaries.

Over the past 45 years, WorldFish has firmly established itself as a global leader in research and innovation in sustainable aquaculture and fisheries. Our work has enhanced the lives of millions of low- and middle-income people who depend on aquatic food systems for food, nutrition, livelihoods and overall wellbeing. Our work is supported by a diverse network of funders and investors aligned to shared goals for positive social, economic and environmental impact. Our teams of science experts and professionals are deployed and conduct work where the greatest sustainable development challenges can be addressed through holistic aquatic food systems solutions.

WHAT ARE

AQUATIC FOODS?

Aquatic foods are aquatic animals and plants grown in or harvested in the wild from water for food or feed, and their synthetic substitutes. They include the following:

FINFISH

Fish as normally understood (e.g. tilapia), which are called finfish to distinguish them from shellfish, which technically are not classed as fish.

SHELLFISH

Any aquatic animal whose external covering consists of a shell, either crustacea (e.g. shrimps) or molluscs (e.g. oysters).

AQUATIC PLANTS

Includes aquatic plants (e.g. watercress) as well as algae (e.g. seaweed) which are typically, not lassified as plants.

OTHER AQUATIC FOODS

Certain niche categories, notably echinoderms (e.g. sea cucumbers) or amphibians (e.g. frogs).

AQUATIC FEEDS

Any of the above categories and other single-celled organisms (e.g. yeasts) used as animal feed.

SYNTHETIC SUBSTITUTES

Whole or component substitutes for any of the above, produced in environments outside their normal biological context (e.g. surimi or plant- or cellbased alternative aquatic food protein).

WHAT IS AN AQUATIC

FOOD SYSTEM?

An aquatic food system is a complex web of:

Elements refer to the environment, people, inputs, processes, infrastructures, institutions, etc.

Activities relate to the production (from wild fisheries, aquaculture and synthetic substitutes), processing, distribution, preparation, consumption and disposal of aquatic foods.

Outcomes are the result of these activities include such as nutrition, health and food security, but also socioeconomic and environmental outcomes.

We use the definition of “food system” by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE) (2017): an aquatic food system is a complex web made up of elements, activities and the outcomes of these activities.

An aquatic food system is sustainable when it ensures food security and nutrition for all in such a way that does not compromise the economic, social and environmental bases to generate food security and nutrition for future generations. Food security and nutrition in this case is not only an outcome but also as an enabling condition of sustainability, and should not be considered a trade-off variable. Aquatic food systems also exist within other systems, such as farming systems, agricultural ecosystems, economic systems and social systems. Within those are further subsets of water systems, energy systems, financing systems, marketing systems, policy systems, culinary systems and so on.

Aquatic food systems, their drivers, actors and elements do not exist in isolation but interact with one another and with other systems, such as tourism, agriculture, health, energy, communications and transportation systems. An aquatic food system includes all the people and activities that play a part in growing, transporting, supplying and, ultimately, eating aquatic foods. These processes also involve elements that often go unnoticed, such as food preferences and resource investments.

Aquatic food systems, their drivers, actors and elements do not exist in isolation but interact with one another and with other systems, such as tourism, agriculture, health, energy, communications and transportation systems. An aquatic food system includes all the people and activities that play a part in growing, transporting, supplying and, ultimately, eating aquatic foods. These processes also involve elements that often go unnoticed, such as food preferences and resource investments.

Population health is a critical factor in addressing aquatic food system challenges, especially as nutrition-related chronic diseases such as obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and some forms of cancer are major contributors to the global burden of disease.

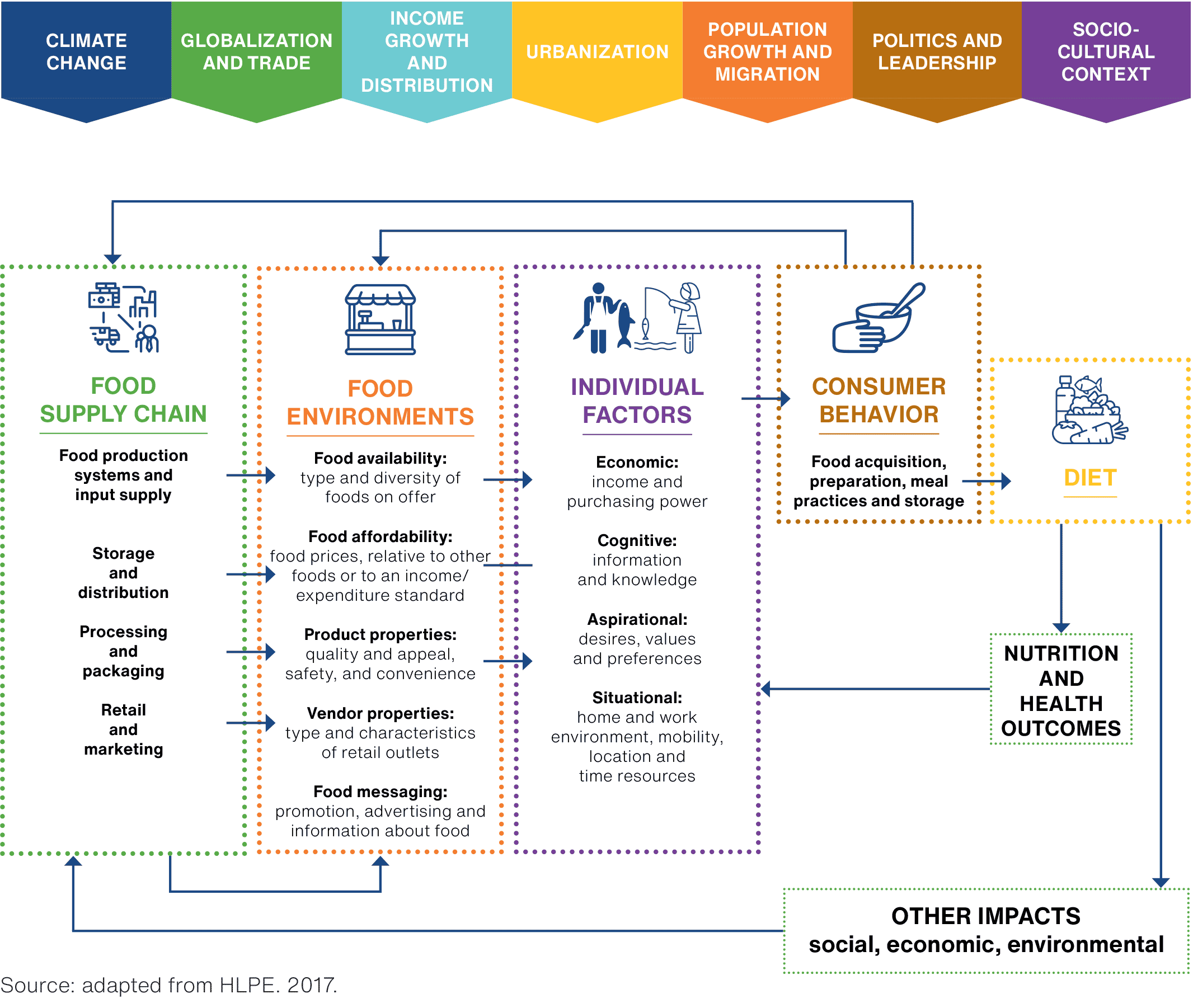

An aquatic food system includes different parts (Figure 1) that shape it and can lead to both positive and negative outcomes. These parts include food supply chains, food environments, individual factors, consumer behavior and external drivers or push and pull factors.

GLOBAL TRENDS

AFFECTING FOOD SYSTEMS

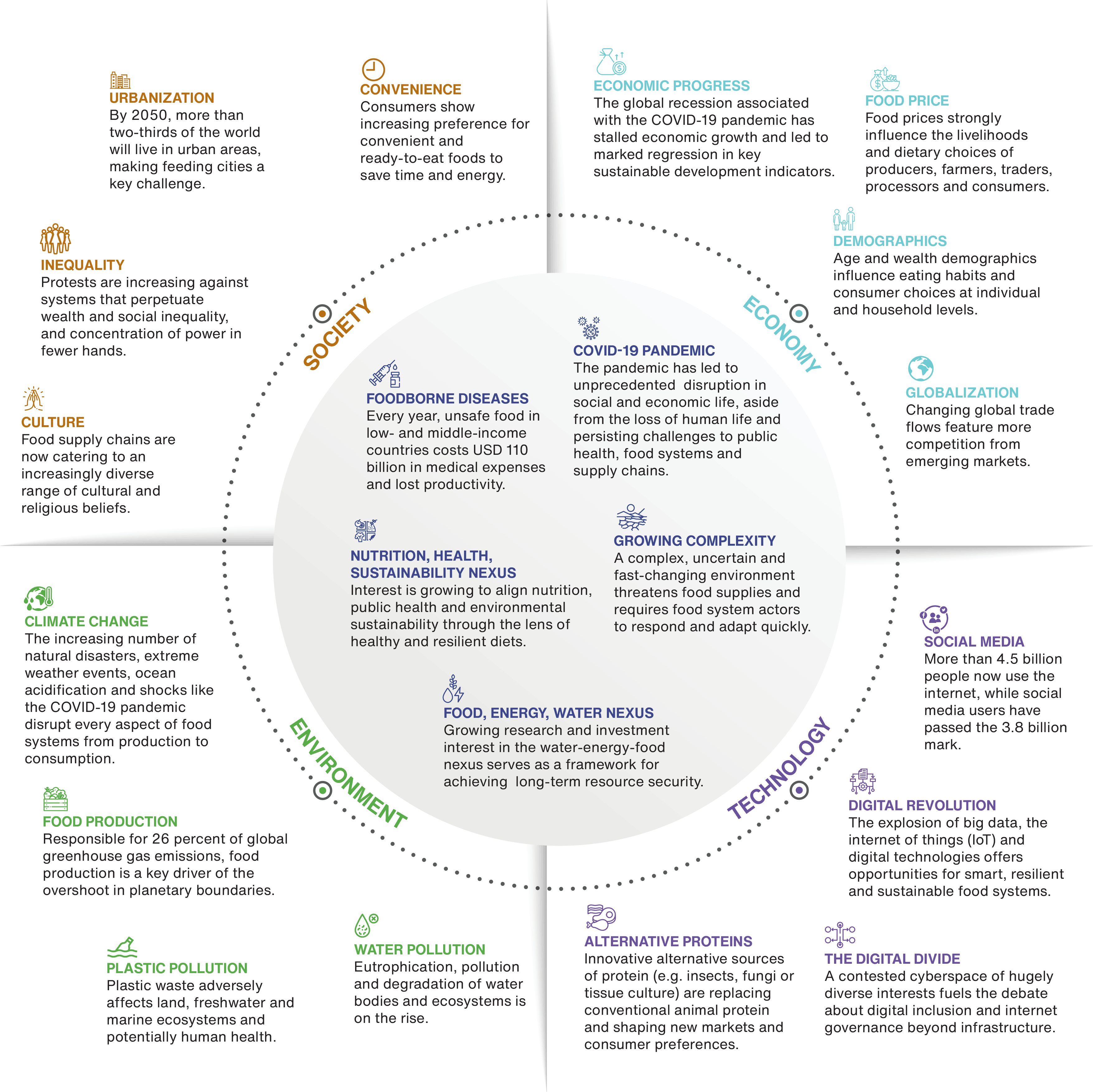

The evolving global context demands a systems transformation approach for food, land and water systems. In devising our strategy, we considered a number of key global trends influencing all food systems over the coming decade. They relate to diverse issues across the environmental, social, economic and technology dimensions of food systems sustainability.

TACKLING GLOBAL CHALLENGES

WITH AQUATIC FOODS

WorldFish is part of the global effort to end hunger and malnutrition, eradicate poverty and address climate change, as well as a number of other interrelated challenges expressed in the 2030 SDGs. The way we grow, catch, store, transport, process, trade, market, promote and consume food from land and water is central to solving critical global challenges and leveraging progress on a number of SDGs. Most of the world’s population eats too little, too much or the wrong combination of food. This comes at an unsustainable cost to our health and well-being, the economy and the environment.

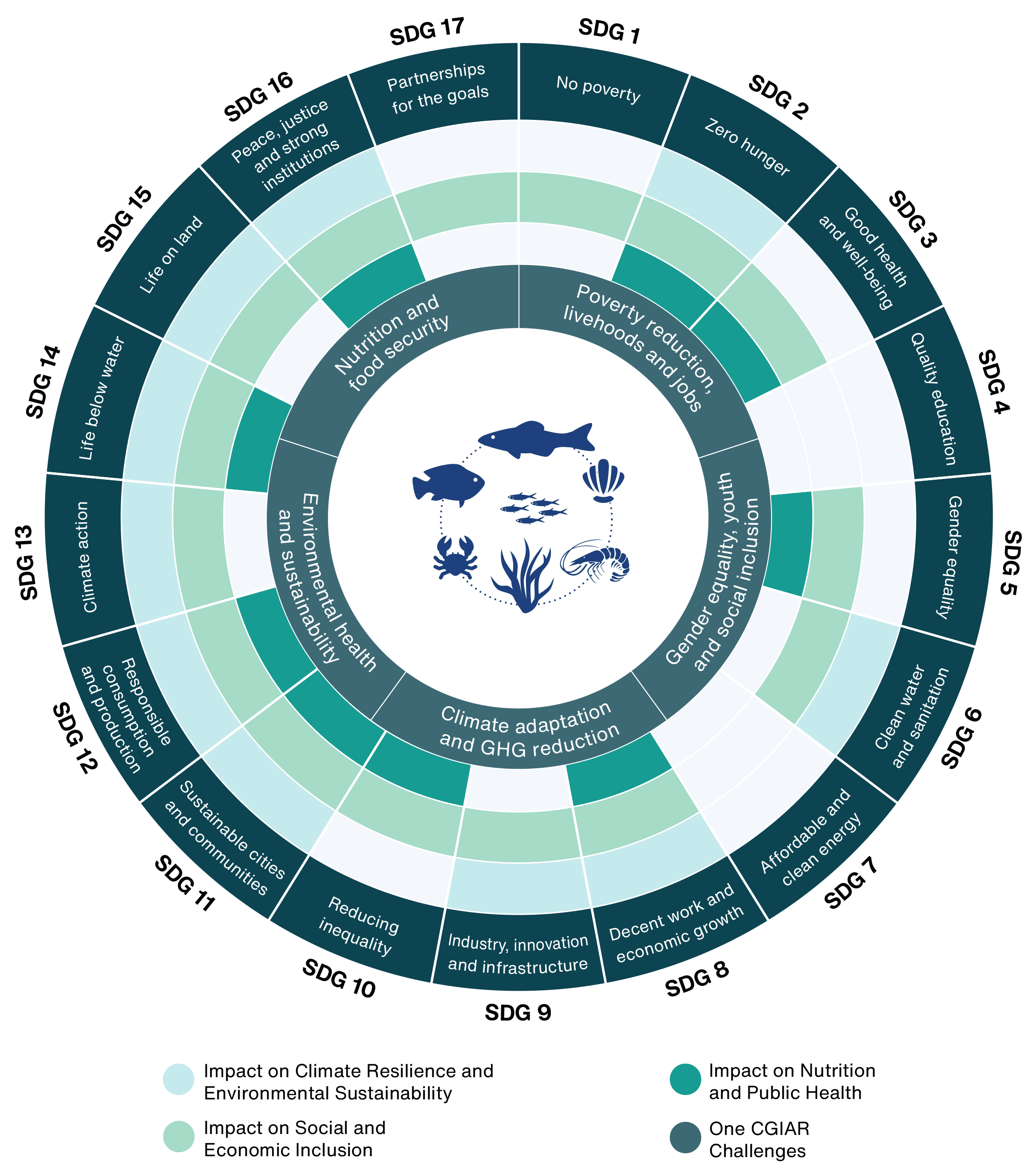

Aquatic foods, alongside land crops and livestock, are a significant part of the equation for healthy and sustainable diets within our planetary boundaries. Our vision, mission and institutional strategy for research on aquatic food systems are aligned with One CGIAR. Our work contributes to the majority of the SDGs, but remains primarily focused on tackling five global challenges targeted by One CGIAR as a collective.

Five global challenges for impact

| One CGIAR impact areas | One CGIAR 2030 success metrics |

|---|---|

| 1. Nutrition and food security |

|

Almost 690 million people (8.9 percent) went hungry in 2019. This number is estimated to grow to between 773 million and 822 million by the end of 2020 because of the food and economic crisis related to the COVID-19 pandemic. High costs and low affordability also mean billions cannot eat healthily or nutritiously. Two billion people do not have regular access to safe, nutritious and sufficient food, and diet-related noncommunicable diseases (such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, cancer and diabetes) are increasing in all regions. If current trends continue, SDG 2: Zero Hunger will not be achieved by 2030. |

Deliver affordable healthy diets to 8.5 billion people, ending hunger and malnutrition for the 2 billion who suffer from macro and micronutrient deficiencies, and reducing diseases related to food systems by one-third. |

| 2. Gender equality, youth and social inclusion | |

Women make up half the workforce and play a prominent role in fisheries and aquaculture economies around the world. They face many inequities in wages and access to productive resources, technology and markets Their work and economic contributions continue to go unrecognized in official statistics, sector policies and development programs. More than 85 percent of the 1.2 billion young people in the world live in low- and middleincome countries, and many of them face limited opportunities for employment, skills development or entrepreneurship. Agriculture, including fisheries and aquaculture, is generally perceived by young people as not the most attractive proposition for decent work, fulfilling livelihoods and well-being. |

Close the gender gap in access to resources, information and power for the 750 million women who work in food, land and water systems, and offer decent opportunities to 267 million young people who are not in employment, education or training. |

| 3. Poverty reduction, livelihoods and jobs | |

Nearly half of the world's population live on less than USD 5.50 a day (the poverty line in upper-middle-income countries). One-quarter live on less than USD 3.20 a day (the poverty line in lower-middleincome countries) and about 689 million people live on less than USD 1.90 a day (extreme poverty). The COVID-19 crisis has made things worse by pushing close to half a billion people back into poverty. Across the world, the fisheries and aquaculture sector is a major source of employment. In 2018, an estimated 59.5 million people were engaged in the primary sector of fisheries and aquaculture. The COVID-19 crisis has already had a disproportionate impact on the poorest and most vulnerable through job loss, loss of remittances, inability to afford healthy and nutritious foods, and disruptions in services such as education and health care. |

Provide living incomes to 1.5 billion people working in food systems, and lift 500 million people above the USD 1.90 a day poverty line. |

| 4. Climate adaptation and greenhouse gas reduction | |

The oceans and coasts provide critical ecosystem services, such as carbon storage, oxygen generation, food and income generation. Coastal ecosystems like mangroves, salt marshes and seagrasses play a vital role in carbon storage and sequestration. Per unit of area, they sequester carbon faster and far more efficiently than terrestrial forests. When these ecosystems are degraded, lost or converted, massive amounts of carbon dioxide (an estimated 0.15–1.02 billion tons every year) are released into the atmosphere or the oceans. Their continued destruction undermines climate mitigation efforts and threatens food security and nutrition for more than 3 billion people who rely on aquatic foods as their primary source of animal protein and other essential nutrients. By virtue of their geography, big ocean states, otherwise known as small island nations, are left physically and fiscally vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, despite having contributed least to it. |

Turn agriculture and forest systems into a net sink for carbon dioxide, and implement all national adaptation plans globally. |

| 5. Environmental health and biodiversity | |

Approximately 65 percent of the world’s population live within 159 km of shoreline, with population growth estimated at 75 percent by 2025. For inland and coastal regions, the ocean provides a unique set of goods and services to society, including moderating climate, processing waste and toxicants, and providing food, medicines and employment for millions of people. Marine biodiversity is being lost at an unprecedented rate as a result of human activities, both direct and indirect, on land and in the water. The percentage of fishstocks within biologically sustainable levels has dropped from 90 percent to 65.8 over the past three decades. |

Stay within planetary and regional environmental boundaries: consumptive water use of under 2500 km3 per year (with a focus on the most stressed basins), zero net deforestation, and nitrogen application of 90 Tg (with a redistribution toward low-input farming systems). |

The specific links between our research work on aquatic food systems, the five One CGIAR impact targets and the SDGs are illustrated in Figure 3.

OUR UNIQUE

PROPOSITION

The world faces the enormous challenge of feeding 9.8 billion people by 2050. Providing affordable, safe, nutritious food for all has become an increasing challenge due to the scale of demand and the increasing threat of climate change (FAO et al. 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic is the latest shock to bring to the forefront fundamental weaknesses in existing global food systems, while taking us further away from the 2030 SGDs (BMGF 2020). Amid growing social inequality and unrest, and with 690 million people worldwide going to sleep hungry every day, we need to fundamentally rethink the way food is grown, produced and distributed.

Aquatic foods offer a viable nutritious and sustainable alternative that is traditionally overlooked in the global agricultural research agenda, which supports sustainable development at country and global levels. Already, about 3.3 billion people worldwide obtain about 20 percent of their average per capita intake of animal protein from fish and aquatic foods (Weeratunge et al. 2013). With more investment in better management and technological innovation, research shows that the ocean and related aquatic food systems can provide over six times more food than they do today. This would be more than two-thirds of the animal protein needed to feed the future global population (Costello et al. 2020).

Aquatic foods are rich in numerous vitamins, minerals, omega-3 fatty acids and other nutrients essential to cognitive development and human health. They could also offer a critical solution for the two billion people worldwide who suffer the triple burden of malnutrition, with women and children poised to benefit the most. Moreover, compared to other animal source foods, many aquatic foods offer multiple nutritional benefits at a lower environmental cost than many land-based animal production systems (Hilborn et al. 2018a).

Fish and other aquatic foods are among the world’s most traded food items, with a total export value of USD 164 billion globally in 2018. They are a highly nutritious food group of major social, cultural and economic significance. They are also big business— the kind of business that does not always favor those most dependent on aquatic food systems for their food, nutrition, incomes and general sociocultural well-being (Hicks et al. 2019a)

Globally, our appetite for aquatic foods shows no signs of slowing (FAO 2020), and changing climate conditions and unexpected shocks, like the COVID-19 pandemic, cause major disruptions on social and economic activities. In a world like this, a diverse range of actors will need guidance and sound scientific data and knowledge to understand the complexity and severity of these issues and to formulate comprehensive responses. Countries looking to meet the SDGs by 2030 need evidence and support (1) to reduce the cost of nutritious aquatic foods, (2) make healthy diets with diverse aquatic foods affordable for everyone, and (3) enable vulnerable—and often invisible—women, men and young people working in aquatic food systems to earn decent incomes that enhance their own health and well-being.

The future contribution of aquatic foods to the global food supply depends on a range of ecological, economic, policy and technological factors (Costello 2019). It also depends on a set of integrated strategies and actions that balance conservation and restoration efforts with food systems transformation efforts (Leclère et al. 2020), across land and water. Delivering healthy and sustainable diets cannot come at the cost of the earth and our health. Our argument is simple. A global food systems transformation toward healthy and sustainable diets that work for people and the planet is not possible without the opportunity to examine, quantify and include the contributions of aquatic food systems to the quest.

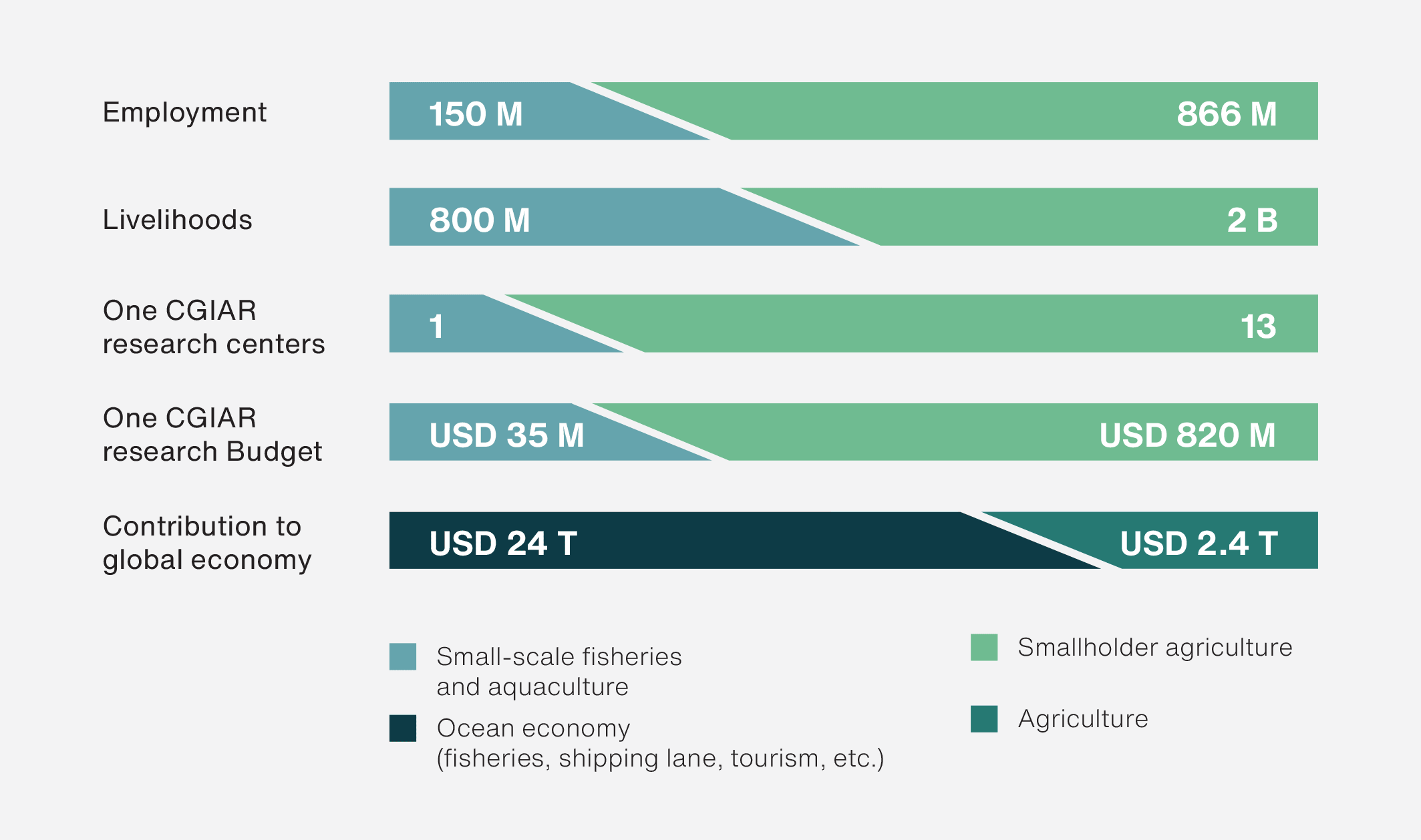

Our priority is to ensure greater integration of fish and aquatic foods into the global agricultural research agenda. Aquatic food, in particular, must be linked to the blue economy and ocean space, whose assets such as fisheries, shipping lanes and tourism are worth USD 24 trillion and produce an annual value of USD 2.5 trillion from their outputs (Hoegh-Guldberg 2015; Österblom 2020). This is critical to ensure a full representation of the food system and to address the complex links between food, land and water systems. It is also critical if we are to unlock opportunities for billions of women, men and young people in low-and middle-income countries through an inclusive and people-centered blue economy and ocean governance.

The Green Revolution, which focused primarily on land crops and livestock, has led to improved food security, nutrition and livelihoods for billions of people over the past 70 years. However, with emphasis on increased crop productivity, its benefits are marked by geographical disparities (Pingali 2012), as well as significant health and environmental costs (Aguilar-Rivera 2019). The next great transformation must therefore involve a transition toward food, land and water systems that are equitable and inclusive, as well as healthy, resilient and sustainable.

The potential impact of linking the global agricultural research and innovation agenda to the blue economy and the ocean space is illustrated in Table 2.

We must rethink production, distribution and consumption of food from both land and water. This requires us to change country and global policies and institutions that enable current agricultural and industrial activities. The practices of over 500 million smallholder farmers must also change as well as the way in which 7.6 billion women, men and children consume food every day. We believe aquatic food systems have an important role to play in meeting the shared global aspiration of establishing inclusive, efficient, sustainable, nutritious and healthy food systems capable of achieving the SDGs without costing the earth. Considering the estimated 10:1 rate of return on investment, research and innovation in aquatic food systems, as an important part of the wider One CGIAR agricultural research agenda, is central to impacts at scale and critical to national and global efforts to tackle climate change, protect nature and biodiversity and boost human nutrition and well-being (Alston 2020).

FOCUS GEOGRAPHIES

AND COMMUNITIES

Over the past 45 years, WorldFish has been building strong and long-lasting partnerships. We have partnered with national governments, local communities, civil society organizations, entrepreneurs, and businesses in countries with high dependence on fish and other aquatic foods for food security and nutrition, as well as jobs, livelihoods and economic growth.

Our global footprint represents more than 20 countries of research interest across Africa, Asia and the Pacific. In many of these countries, we have a physical presence and our research teams are placed to work alongside national agricultural research institutions or relevant government ministries. Together, we support and strengthen local capacities and skills for scientific research and data, as well as research-to-policy program development, management and implementation. At the regional level, our work with One CGIAR partners connects us to key regional economic actors and intergovernmental organizations that shape discourse, policy and practices for sustainable development across the continent.

Over the next 10 years and within One CGIAR centers, our intention is to expand our geographical footprint in key countries and communities in Africa, Asia, the Pacific, and Latin America and the Caribbean, where our work can make a difference to persisting development challenges.

Through the use of global assessment indicators, we have defined our priority countries. These are nations where research on aquatic food systems can have a significant impact on millions of people whose livelihoods and futures are dependent on aquatic foods. They also are heavily impacted by the five One CGIAR grand challenges:

- Nutrition and food security

- Poverty reduction, jobs and livelihoods

- Gender equality, youth and social inclusion

- Climate adaptation and greenhouse gas reduction

- Environmental health and biodiversity

Africa faces extreme poverty and food and nutrition security challenges. More than 40 percent of the population lives on less than USD 1.90 a day, and nearly one in three Africans do not have enough to eat. Demand for food will grow as the continent’s population is set to double to 2.4 billion by 2050. African cities are already the fastest growing in the world. By 2050, the continent will be home to up to 15 megacities of more than 10 million inhabitants.

Fisheries and aquaculture play a significant social and nutritional role and directly contribute USD 24 billion to the African economy. They represent a critical social safety net and source of food and nutrition, particularly in times of successive crop failures and poor agricultural harvests, or other humanitarian emergencies related to climate change or conflicts. The sector employs over 12 million people, a quarter of whom are women engaged in postharvest fish processing and trade activities. The economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has plunged the continent into its first economic recession in 25 years, resulting in a loss of jobs and incomes for one-third of the entire workforce.

On average, fish and aquatic food products account for 19 percent of animal protein intake among African consumers. However, consumption of fish and aquatic foods in Africa remains half the global average of 20.8 kg per capita annually. Wild capture fisheries supply most of the fish and aquatic foods, but they face enormous challenges of overexploitation and a lack of sustainable management. Illegal unreported and unregulated fishing costs West Africa alone USD 1.3 billion per year. With rising sea temperatures, harsher weather conditions and the migration of fish to cooler waters, climate change threatens aquatic food supplies locally.

The continent relies on imports to meet growing fish demand. Sub-Saharan Africa has the world’s highest rates of vitamin A deficiency in children and iron deficiency in women, and populations in East and Southern Africa are chronically undernourished. And in West and Central Africa, people have the world’s highest per capita incidence of foodborne diseases.

As an essential source of micronutrients and animal protein, safe and nutritious aquatic foods can help address these issues through increased consumption. The emergent aquaculture sector requires significant investment in skills, knowledge and inputs in order to take off. Investments in improved fisheries management systems and appropriate infrastructure are critical to enhancing resilience to the impacts of climate change and making aquatic foods accessible and affordable for low-income domestic consumers.

Countries of interest

Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Zambia

Regional partnerships and unions

AU, AfDB, ASARECA, CCARDESA, CAADP Reporting Framework, COMESA, CORAF, ECOWAS, ECCAS, EAC, FARA and SADC

One CGIAR Region

Central & West Asia & North Africa (CWANA), West & Central Africa (WCA), East & Southern Africa (ESA)

Despite its strong economic growth, Asia is home to an estimated 400 million people living in extreme poverty below USD 1.90 a day. The number of people living at the higher poverty line of USD 3.20 a day is 1.2 billion, which accounts for more than a quarter of the region’s population. Asia is home to seven of the 10 most densely populated cities in the world, yet a large share of Asia’s population still lacks access to basic infrastructure and services. Existing infrastructure development and growth patterns can lock cities into unsustainable consumption and production models for years to come.

The main human and environmental health challenges relate to poor air quality, a lack of clean water supply, and mismanagement of waste and sanitation. Vitamin A, zinc and iron are three of the most significant micronutrient deficiencies, and they remain a serious public health risk in South and Southeast Asia. More than two-thirds of all wasted children under 5 years of age and approximately 83.6 million (55 percent) of all stunted children live in Asia.

The region is the world’s largest producer of aquatic foods from both aquaculture and capture fisheries. Most of the growth comes from China and from countries in South and Southeast Asia. Overall, Asia is home to 85 percent of the world’s fishers and aquaculture workers. Production from many small-scale operators in inland areas of the region often goes unrecorded. Currently, there is a rapid, ongoing shift in the supply of freshwater fish in Asia, from wild to farmed sources. This represents an important, yet poorly understood food transition with critical ramifications for addressing the region’s sustainable development in the context of rapid urbanization, rising incomes and changing diets. Climate change poses a major threat, with an increase in flooding and salinization in coastal areas and major deltas, which are the region’s densely populated food baskets. In addition, plastic pollution threatens marine biodiversity, and the estimated damage to key marine ecosystems of the region, including the Bay of Bengal, costs up to USD 13 billion annually.

Consumption of aquatic foods is growing in Asia. Several factors are driving this increase, including urban population growth, rising incomes, expanding international fish trade routes and a dramatic extension of fish production, especially from aquaculture. Southeast Asia has the highest rate of annual fish consumption in the world at over 35 kg per capita. Domestic consumers and their access to balanced, healthy diets with safe and affordable foods are as diverse in their preferences as the aquatic food products they consume due to local, cultural, economic and geographical differences. And demand for high-value fish species, which consume high-quality feeds, is increasing among urban populations.

To secure healthy and sustainable diets for all, more research and investment are required. What is needed are well-integrated policies, technologies, infrastructure and value chains that balance economic growth with considerations of food security and nutrition, gender and social inclusion, climate resilience and environmental protection.

Countries of interest

Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Vietnam

Regional partnerships and unions

SAARC and ASEAN

One CGIAR Region

South Asia (SA); Southeast Asia & Pacific (SEA)

The Pacific region is an ocean of islands with mostly low- and middle-income countries populated by some of the world’s most at-risk societies. Poverty, exclusion and vulnerability are on the rise in Pacific island countries, with one in four individuals living below USD 1.90 a day (UNDP 2014). Pacific communities are defined by their relationship to the ocean. The region is rich in natural wonders, cultures and traditional practices and boasts spectacular diversity. Aquatic foods are the backbone of Pacific island economies. Coastal fisheries generate food and income for low-income rural communities, particularly where formal markets and supply chains function poorly.

Economies are shifting from traditional systems built on the exchange of products to market-led cash-based ones. Young people are migrating from villages to find jobs in cities and abroad, leaving women, the very old and the very young behind. There is also a lack of broader development in a variety of areas, including infrastructure, communication, banking and public services. As a result, it is difficult and expensive to transport and distribute highly perishable fresh foods from the garden or the ocean to urban marketplaces. This has driven the growing influx and acceptance of refined, processed and nonperishable convenience foods, which have a long shelf life. Paradoxically, these foods are more affordable, accessible and available than domestically harvested fish and vegetables in urban settings.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), nine of the 10 “most obese” countries of the world are in the Pacific. Noncommunicable diseases related to malnutrition are the leading cause of premature death and disability in the region—principally cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes and chronic respiratory diseases. Several of the Pacific island countries also have a high prevalence of stunting in children under 5 years of age.

Population growth, pollution, overfishing and climate change threaten the future supply of aquatic foods and exacerbate food security and nutrition challenges in the region, yet Pacific island communities contribute the least to climate change. By virtue of their geography, however, they are among the world’s most vulnerable people when it comes to severe climate impacts related to sea-level rises, changing temperatures and extreme natural events. These impacts will affect food and water security, loss of identity, climate-induced migration and threats to sovereignty.

In response, communities in the region are leading climate adaptation strategies. Often in combination traditional knowledge and practices with cutting-edge science, these strategies are building the resilience of their communities and ecosystems in the face of increasing climate risk. By necessity, Pacific islands are becoming hubs of innovation, where climate strategies can be piloted, refined and scaled to inform successful climate adaptation efforts in other large ocean states, as well as globally.

Countries of interest

Solomon Islands, Timor-Leste

Regional partnerships and unions

Pacific Island Forum

One CGIAR Region

Southeast Asia & Pacific (SEA)

More than 80 percent of people in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) live in cities, but this rapid urban growth in the region poses challenges. These include profound social-economic inequality, limited mobility, pollution, increased vulnerability to natural hazards, poor urban planning, high levels of unemployment, crime and weak institutional and fiscal capacity, among others.

On average, one in five people in the region live in chronic poverty, and every year 600,000 people die due to diseases related to poor diets, such as diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. Inadequate diets are associated with more deaths than any other risk factor. In addition, the rates of both childhood and adolescent obesity have tripled between 1990 and 2016.

People in LAC have the lowest annual per capita consumption of fish worldwide at only 9.8 kg. This stands in stark contrast to the region being a net exporter of fish and aquatic foods and a large aquaculture producer. Peru is the world’s top producer and exporter of fishmeal and fish oil. Since 1980, aquaculture production in LAC has increased 100fold, and the sector employees 3.8 million people. Meanwhile, small-scale fisheries support livelihoods, employment and food security of more than 2.3 million people in marine, brackish and freshwater environments. They contribute to environmental stewardship in the region, which is known for its rich biodiversity and endemic species. The Amazon basin alone is home to more than 3000 fish species and represents one in every 10 freshwater fish caught worldwide. Households in the Brazilian Amazon obtain 30 percent of the family income from fishing. Yet despite their high social and economic relevance in the region, small-scale fisheries are characterized by a history of inequality, social exclusion and invisibility in key policies.

By 2030, production from both aquaculture and fisheries in the region is expected to grow by 24 percent, from 12.9 million tons to 16 million tons. While food availability in the LAC region is sufficient to meet the energy needs of its entire population, there are worrying trends. Per capita consumption of sugar and fats is higher than the recommended range for a healthy diet, while the availability of fish and aquatic foods per capita is the lowest in the world.

Research and investments are required to support the adoption of healthy eating habits and changes in public policies. The purpose is to create sustainable and nutrition-sensitive food systems that provide healthy aquatic foods for all, while preserving land and aquatic food ecosystems through sustainable use of natural resources, and improved techniques for food production, storage and processing.

Countries of interest

Colombia, Honduras, Mexico, Peru

Regional partnerships and unions

CELAC

One CGIAR Region

Latin America & the Caribbean (LAC)

WHO BENEFITS

FROM OUR WORK

In our focus countries, many women, men and young people are engaged in small-scale fisheries and/or small and medium aquaculture, as producers, consumers of aquatic foods, and workers and business owners in related value chains. They are the principle focus of our work.

These groups often remain marginalized, underserviced or overlooked despite the important contributions they make to local and national economies and food security. Our research informs policy, market, institutional and technological innovations that prioritize rights and access to natural resources, land, assets, technologies, public services and finance so that people in these groups can determine their own lives and futures.

Working as a networked organization is what supports our multistakeholder engagement approach. We use formal and informal approaches, participatory research methods, space for dialogue, and proactive engagement in the wider innovation ecosystem. Together, they enable different actors with various skillsets, experiences, sector and discipline backgrounds to connect, learn, exchange knowledge and co-create solutions.

A snapshot of how different groups of stakeholders benefit from our work on aquatic food systems is provided below.

SMALL-SCALE FISHERS, FARMERS, PRODUCERS, PROCESSORS,TRADERS AND CONSUMERS

- These actors gain greater access to knowledge, inputs, finance, innovations and business opportunities that boost incomes, create jobs, reduce loss and waste, and improve nutrition, health and well-being.

- People living in low- and middle-income countries gain greater availability, accessibility, variety and consumption of aquatic foods.

- Consumers in low- and middle- income countries make better and informed choices about aquatic foods as part of healthy and sustainable diets.

- Local knowledge, needs, voices, priorities and perspectives of people dependent on aquatic food systems shape the development of an inclusive and people-centered blue economy and ocean governance.

LOCAL COMMUNITY AND DEVELOPMENT ACTORS

- Local actors participate in and contribute to cutting-edge research on sustainable aquatic food solutions that deliver multiple benefits for vulnerable and disadvantaged communities.

- They gain access to open-source scientific and practical knowledge on best practices and low-cost technologies to shape community-based solutions.

- Research guides and supports the development of social protection schemes, community development programs and interventions based on the latest scientific evidence, data and decision-making tools.

- Greater knowledge and expertise are shared and transferred between communities, civil society organizations, social entrepreneurs, local development actors and our scientists and partners, accelerating sustainable and inclusive transformation at all levels of the food systems.

SCIENTIFIC COMMUNITY IN LOWAND MIDDLE-INCOME COUNTRIES

- Scientists in the Global South benefit from increased engagement and collaboration with WorldFish, One CGIAR and partners in the wider international scientific community.

- New research and development projects focus on aquatic food systems and related issues, such as nutrition, climate change, public health, gender and social inclusion.

- Critical data, insights and perspectives from scientists and communities in the global South are increasingly included in global policy and change agendas.

- Greater knowledge and expertise are shared and transferred between scientific institutions in the Global South and North, sustaining continued innovation and accelerating food systems transformation.

PUBLIC SECTOR

- Policymakers at all levels increase knowledge and understanding of scientific evidence on aquatic foods and use innovative data-driven tools related to shaping multisectoral policy and investment decisions with interrelated social, economic and environmental impact.

- Policymakers increasingly recognize the significant role of aquatic food systems in meeting national SDG targets on climate action, gender equality, nutrition, decent work, responsible consumption, etc.

- They strengthen their own research and policy development capacities on issues related to aquatic food systems.

- They learn about innovative solutions in other communities and geographies and are able to adopt, adapt and implement these in their own contexts.

- They benefit from increased networking opportunities with science, market and other actors with critical knowledge, tools and resources required to develop shared solutions with aquatic foods to deliver multiple social, economic and environmental benefits.

- Statistical information systems on aquatic foods, at national, regional and global levels, are improved and developed for better policies and decisions.

ONE CGIAR

- A more inclusive and relevant global research agenda on food, land and water systems includes aquatic food systems and the billions of people dependent on them.

- Research, engagement and investment opportunities are expanded with new public and private sector collaborations through greater focus on aquatic food systems research.

- One CGIAR's relevance and influence in the world is increased through stronger connection to important future food areas related to the blue economy.

MEDIA AND THE GENERAL PUBLIC

- Media at all levels shape public opinion, discourse, narratives and individual behaviors and change agendas based on objective and impartial scientific facts, knowledge and insights.

- Research helps to inform public debate, dispel myths and misconceptions about key issues of critical public interest, and to inspire action for a sustainable food systems transformation at all levels.

- Increased interest and engagement with science helps to shape better narratives, improve discourse and brighten futures with aquatic food systems.

PRIVATE SECTOR

- Businesses, local cooperatives and social entrepreneurs in low- and middle-income countries benefit from increased scientific knowledge, networks and collaboration on new aquatic food technologies, practices and innovations ripe for scaling and development.

- A growing aquatic foods sector in low- and middle-income countries benefits from a skilled workforce and entrepreneurs armed with the latest scientific knowledge and training in aquatic foods technologies and best practices.

- Engagement with researchers, policymakers and other critical stakeholders allows for new discoveries and sustained innovation at the cross-section of sectors and disciplines.

- New jobs and entrepreneurship opportunities are created in an inclusive blue economy that is powered by digital technology.

- Research guides the development of market-based standards and certifications for nutritious aquatic food products that are socially and environmentally responsible.

YOUNG SCIENTISTS, INNOVATORS AND ENTREPRENEURS

- Young women and men in low- and middle-income countries build skills, knowledge, capacities and gain access to critical development opportunities and resources to shape their future careers in academic, policy or business.

- They gain exposure and real-world experience from involvement in cutting-edge research and development projects in aquatic food systems.

- Young innovators and entrepreneurs develop policy, market and technology solutions based on scientific evidence.

- They receive support and mentorship from world-class scientists and are given access to prestigious science, policy and business networks through WorldFish, One CGIAR and other public and private sector partners.

INVESTORS, PHILANTHROPIC ACTORS AND DEVELOPMENT AGENCIES

- Investors across the public and private sectors discover and fund winning science, technology, policy and market innovations in aquatic food systems that deliver multiple and inclusive outcomes for improved health and nutrition, climate action, environmental protection, etc.

- Scientific data, knowledge and evidence support the business case for increased investments, research and innovation in aquatic food systems.

- Critical investment decisions on policy, market and consumer incentives to fulfill the sustainable development potential of aquatic food systems are guided by sound evidence.