PART II

A TRANSFORMATIVE AGENDA FOR RESEARCH ON AQUATIC FOOD SYSTEMS

WorldFish 2030 Research And Innovation Strategy

DownloadTHE UNTAPPED POTENTIAL OF

AQUATIC FOODS

Our agenda for research on aquatic food systems reflects the call for a radical transformation of food systems by the HLPE. Transforming food systems to deliver healthier and more sustainable diets is imperative if we are to meet the needs of all within the means of the planet. This will ensure that no one falls short on life’s essentials, while making sure we do not overshoot the earth's life-supporting systems (Raworth 2017), which are the “planetary boundaries” (Rockström 2009). This imperative reflects and is intensified by the context of climate change, the growing triple burden of malnutrition, and widening economic inequality. Aquatic food systems are an extremely important but historically undervalued component of the global food system and their role in improving nutrition and sustaining healthy diets (Thilsted 2016). Aquatic foods share three sets of important characteristics that lend them an outsized role in meeting the grand challenge of transforming the food system to deliver better human and environmental health outcomes.

ENVIRONMENT

Aquatic foods are highly diverse (Tlusty et al. 2019). They also tend to have much lower average resource use and environmental impact profiles than land-based animal-source foods such as beef and pork (Willett 2019; Froehlich 2018; Hilborn et al. 2018b). For instance, beef cattle create greenhouse gas emissions that are eight times greater on average than those from farmed fish (Poore and Nemecek 2018). In addition, fish are cold-blooded, so they are able to convert protein and energy to body mass more efficiently than warm-blooded terrestrial animals. Most feed ingredients used to raise farmed fish are by-products of crop production, such as rice bran and oil cake. At least one-quarter of all fishmeal is now obtained from fish processing waste, which contributes significantly to the circular economy (Stevens et al. 2018). Seaweeds and filter feeding molluscs, such as mussels, are grown without any feeds or fertilizers and can sequester carbon dioxide and improve water quality by stripping nutrients (Fodrie et al. 2017). When well managed, wild stocks of fish and other aquatic animals are important renewable resources that can be harvested indefinitely at sustainable levels.

LIVELIHOODS

Fisheries and aquaculture are important sources of jobs, employment and income for millions of people in Africa, Asia and around the world (Phillips et al. 2016; World Bank 2008). Employment is full- and part-time, and both direct (for fishers or farmers) and indirect (for workers in and owners of a plethora of small and medium enterprises that provide supporting services along aquatic food value chains) (Hernandez et al. 2018). Fisheries can serve as an important social safety net, absorbing seasonal surpluses of labor (Béné et al. 2010). They can also be more lucrative for participants than alternative sources of employment and can provide investment capital for other household enterprises (Allison and Mvula 2002). Women account for approximately half of the people employed in fisheries globally when work onshore is also included (Weeratunge et al. 2011). Aquaculture typically generates much higher returns than crops such as rice, contributing to the sector’s rapid growth. It is also often more labor intensive than seasonal agriculture, which creates demand for jobs year-round both on- and off-farm (Filipski and Belton 2018), including for many young people.

NUTRITION

Fish and aquatic foods are the main animal-source food consumed by more than a billion “fish dependent” people. They are an irreplaceable source of micronutrients, essential fatty acids and high-quality protein for the most vulnerable in many of the world’s lowest-income countries in Africa, Asia and the Pacific (Golden et al. 2016; Hicks et al. 2019b). In these regions, there is an outsized contribution of aquatic foods to diets and micronutrient intakes in low- and middle-income countries. This makes maintaining and increasing their accessibility and availability key to addressing undernutrition. Moreover, aquatic foods are the primary source of omega-3 fatty acids. These are essential for cognitive development, and they reduce the risk of noncommunicable diseases. They also have an important role to play in combating the risks associated with overweight and obesity, making them a healthy alternative to red meat and poultry (He 2009).

Aquatic food systems have enormous potential as a lever for transformation toward a more sustainable and equitable global food system. A series of critical challenges described on page 34 undermine their current positive contributions or prevent them from delivering their full transformative potential.

KEY CHALLENGES TO

AQUATIC FOOD SYSTEMS

Impacts of climate change affect the productivity and viability of fisheries and aquaculture. These include higher water temperatures, salinity, severity and frequency of droughts and floods, and ocean acidity, all of which can increase vulnerability and risk and erode productivity, profitability and resilience (Barange et al. 2018).

Competition for resources used in the production of feeds (including land and freshwater used to grow terrestrial crops) and forage fish make it essential to use and allocate existing resources more efficiently and equitably and reduce loss, waste and environmental externalities.

The “blue acceleration” of escalating competition for space in the oceans for purposes as diverse as undersea mining, tourism and conservation (Jouffray et al. 2020) make it essential to advocate for equity and justice in the emerging blue economy to prevent the exclusion of fishers and other traditional users from access to aquatic resources on which they depend (Cohen et al. 2019).

Infrastructure development and land use change such as dam construction, conversion of biodiverse habitats like wetlands and mangroves, as well as overfishing and pollution, are sometimes consequences of aquatic food production and can seriously threaten its future viability.

Work in aquatic food supply chains can be risky or dangerous and is sometimes highly exploitative, as revealed by a series of recent “slavery scandals” (Marschke and Vandergeest 2016). Opportunities to participate productively in aquatic food production are not accessible to all, with gender and other forms of identity sometimes serving as a basis for social exclusion.

In some low- and middle-income countries with high levels of aquatic food consumption, changing food environments and shifting opportunity costs of time are encouraging consumption of less healthy food. This requires a shift to more convenient product forms to sustain optimal levels of consumption.

Aquatic animal diseases are an increasing challenge for aquaculture and a major cause of risk, instability and financial loss in the sector. Aquatic animal health is linked to human health through use of antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance (Cabello et al. 2013), while food safety is a key factor driving the restructuring and governance of aquatic food supply chains in middle-income countries, with potentially inequitable outcomes for smaller producers (Belton et al. 2020).

Declining availability and diversity of wild aquatic foods also threatens food and nutrition security.

RESEARCH PRIORITIES

FOR ACTION

Our research response is designed explicitly to address the types of challenges described on page 34. As a result, our strategy on research and innovation will contribute to the sustainability of aquatic food systems specifically and food systems in general, and unlock opportunities to transition and shift these to deliver healthy, resilient diets and shared prosperity for all.

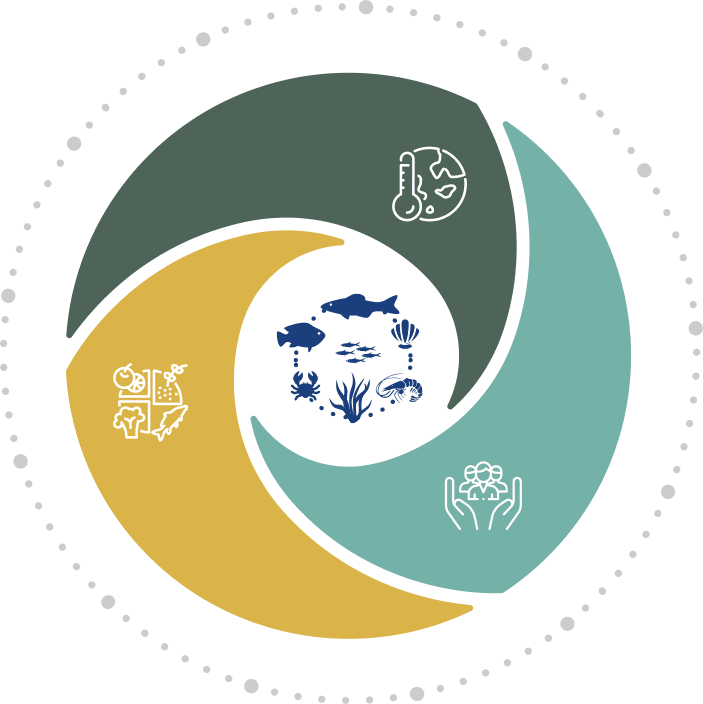

Our transformative agenda for research on aquatic food systems will focus on three main areas of impact that are crucially important: (1) climate resilience and environmental sustainability, (2) social and economic inclusion, and (3) nutrition and public health (Figure 4). The shift toward food systems research takes into account the four dimensions of natural, produced, human and social capital in food systems, from production through to consumption (Kumar 2010).

Our research activities are structured around nine priority actions that respond to the five One CGIAR impact areas and the SDGs. These actions deliver measurable impacts through an integrated set of indicators to evaluate and track progress toward healthy and resilient diets and food systems sustainability, which is a critical step in building national transformative pathways (Chaudhary et al. 2018).

Drawing on an extensive consultation and assessment of challenges in the focus geographies and communities described in Part I of the strategy, we have built on the areas of work where WorldFish has its strongest value proposition and legacy of impact. Based on emerging trends, we have canvassed new opportunities, particularly in the areas of the blue economy, big data and digital technologies, alternative proteins, circular economy approaches to food loss and waste, as well as One Health considerations for people, animals and the environment.

Research priorities for action.

1. IMPACT: CLIMATE RESILIENCE AND ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY

- Enable sustainable production of diverse aquatic foods

- Cut down on loss and waste

- Enhance climate resilience and reduce greenhouse gas emissions

2. IMPACT: SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC INCLUSION

- Leave no one behind with an inclusive and peoplecentered blue economy

- Improve the availability, accessibility and affordability of aquatic foods for all

- Support sustainable livelihoods, decent work and well-being

3. IMPACT: NUTRITION AND PUBLIC HEALTH

- Inform consumer demand for healthy and nutritious aquatic foods

- Ensure aquatic foods are safe and healthy for human consumption

- Prioritize nutrition and health for vulnerable and marginalized people

Details of these priority actions for research, including activities, related food system sustainability indicators, links to the five One CGIAR impact areas and the SDGs, as well as key One CGIAR and other partners, are outlined in the next section.

IMPACT AREA 1:

CLIMATE RESILIENCE AND ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY

Strategic research objective 1

To discover, develop, test, adapt and promote science-based innovations, technologies and practices that reduce climate risk through sustainable use and management of aquatic resources.

About 3.3 billion people worldwide rely on wild-caught and farmed aquatic foods as their main source of animal protein (FAO 2020). The livelihoods of millions of people depend on marine and freshwater resources and related ecosystem services. These ecosystems are under immense pressure due to overexploitation, habitat degradation, greenhouse gas emissions, agricultural and industrial land conversion, depleted water resources, plastic and runoff pollution, and the unsustainable way in which food is generally produced and consumed. These climate change pressures exacerbate the situation through gradual warming, ocean acidification and changes in the frequency, intensity and location of extreme events. In turn, these negatively impact the productivity of aquatic resources across multiple trophic levels. Studies show that actions to curb greenhouse gas emissions are critical to prevent the estimated 40 percent decline in tropical fish catch globally by 2050 (Lam 2020). On the other hand, up to 35 percent of fisheries and aquaculture production is either lost or wasted (FAO 2020). Coupled with continued overconsumption and rising incomes in transitional economies, this will put further strain on the environmental sustainability of food systems (HLPE 2014).

The compounded impacts of climate change and unsustainable use of marine and freshwater ecosystems are compromising their provisioning and general life support services. Our work will focus on reversing this trend and accelerating the transition to ecosystem restoration. Food system approaches will provide the market framing for research on aquatic food production (including marine and inland fisheries, aquaculture and integrated land and water farming). We will generate evidence and innovations to reduce food loss and waste, build climate resilience and put aquatic food production systems on a low emissions pathway toward environmental sustainability. We will also address the challenges facing small-scale fishers, fish farmers, processors and traders who are unable to leverage market opportunities due to a low asset base, exposure to risks, geographical isolation and social exclusion.

One CGIAR impact themes

Climate Adaptation and Greenhouse Gas Reduction

• Environmental Health and Biodiversity

Food system sustainability indicators:

Ecosystem Stability • Ecosystem Services • Conservation and Sustainable Use of Biodiversity • Resource Efficiency • Reduction in Food Loss and Waste • Climate Change Mitigation • Resilience

SDGs

Enable sustainable production of diverse aquatic foods

Diverse food production systems provide the foundation for dietary diversity, food system resilience and environmental sustainability. Diversity has multiple benefits at multiple nodes within the food system, from smallholder integrated farming systems, to small-scale fisheries, through to globally traded aquatic foods. Scientific evidence to inform policy and investment decisions is critical here. Research will identify innovative solutions to sustainably harvest and produce diverse aquatic foods from capture fisheries and aquaculture, as well as integration with landbased food production systems.

Inland and coastal fisheries are vital to the nutrition, food security and livelihoods of millions of people in low- and middle-income countries. Since 1990, the percentage of fishstocks within biologically sustainable levels has dropped from 90 percent to 65.8 (FAO 2020). Although progress is being made globally in improving fisheries management, many fisheries within low- and middle-income countries remain poorly managed. Despite their importance to large numbers of people around the world and the significance of the threats they face, fisheries continue to receive limited attention from policymakers. This is because a large proportion of fish in developing countries is supplied by small-scale fisheries, whose contribution is often unaccounted for in national statistics. Moreover, short-term profits are often prioritized at the expense of long-term viability due to limited incentives and misallocated investments. Building on our groundbreaking work with the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and Duke University on Illuminating Hidden Harvests (WorldFish n.d.), we will continue to work with diverse stakeholders to advance understanding of the value of capture fisheries and increase efforts to capture their contributions in national accounts. We will use quality data to inform policy and investment decisions, align incentives and investments, and cohost platforms for dialogue at national, regional and global levels. This will accelerate the transition toward socially inclusive and environmentally sustainable capture fisheries.

Aquaculture is the fastest growing food-producing sector in the world. Since 1970, it has averaged an annual growth rate of 7.5 percent (FAO 2020), and it is becoming a key source of sustainable animal-source foods. Meeting future demand will require sustainable intensification of aquaculture systems and scaling of game-changing aquaculture innovations in those countries facing fish and aquatic food deficits, while managing any social and environmental risks. Our work with private and public partners will focus on three areas: (1) generating knowledge and tools for sustainable feeds and feed systems, (2) preventing and controlling animal diseases, and (3) enhancing the environmental sustainability of aquaculture production systems, while ensuring improved nutrition, health and socioeconomic outcomes for all.

Our groundbreaking work on genetically improved and resilient fish breeds, including application of innovative genomic technologies, will continue. We will work with partners to ensure improved breeds are accessible and widely disseminated, while examining critical market forces, including certification schemes, to shape, inform and incentivize transformation toward sustainable aquatic food systems, from production to consumption. At the global level, as part of the Committee on Fisheries (COFI) Advisory Working Group on Aquatic Genetic Resources and Technologies, we will continue to support the development and implementation of the Global Plan of Action on Aquatic Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, in partnership with FAO.

Finally, we will seek to integrate aquatic food production into water and land systems at landscape and watershed levels in ways that sustain and diversify food production within environmental limits. Promising research, such as the integration of fish into water management schemes, nature-based solutions, nutrition-sensitive approaches to integrated farming systems of crops, livestock and aquatic foods, will be scaled to increase sustainable production of diverse aquatic foods and to improve outcomes for millions of people who depend on them for nutrition, health, jobs and livelihoods.

One CGIAR partners

IWMI, ILRI, CIFOR, CIP

Research partners

Roslin Institute, CIRAD, JCU, WUR, CEFAS, national research partners

Policy and advocacy partners

FAO, IFAD, ministries in partner countries

Cut down on loss and waste

Thirty-five percent of the global harvest from fisheries and aquaculture is lost or wasted. The value of discarded fish alone is estimated to be worth USD 22.5 billion per year (FAO 2020). Aside from the environmental imperative to improve the sector’s efficiency and sustainability, tackling loss and waste in aquatic foods offers other opportunities to address related losses in nutrition, livelihoods and public health. This can be accomplished through innovative technologies, products and services that are supported by appropriate policies, regulatory frameworks, capacity building and improved infrastructure, as well as access to markets. However, critical gaps in data and knowledge must be tackled to minimize and, where possible, eliminate loss and waste across aquatic food supply chains in low- and middle-income countries. We will work with partners to fill these gaps, as well as identify and evaluate innovation opportunities to co-develop new commercially viable products, services and markets to unlock new value from loss and waste.

We will work with multidisciplinary and cross-sector partners to establish an open innovation lab for co-designing and accelerating disruptive market, product, technology and social innovations. These innovations will provide multiple benefits for low- and middle-income producers, farmers, processors and consumers of aquatic foods. In addition, we will work to incubate and scale promising research with public and commercial partners representing fisheries, tourism, restaurant, food and beverage, cosmetics, pharmaceutical and other sectors. We will explore novel methods of engagement with various stakeholders to increase awareness about loss and waste in aquatic food systems and influence behaviors and investments toward eliminating it.

One CGIAR partners

IFPRI

Research partners

NRI, University of Greenwich; Johns Hopkins University

Policy and advocacy partners

FAO

Enhance climate resilience and reduce greenhouse gas emissions

Aquatic food systems are complex nonlinear systems that involve multiple actors and varying networks and interactions. The complex interrelated impacts of climate change and aquatic food systems, and their implications for ecological, economic and social systems, can only be understood and addressed through an integrated systems approach. This requires a shift from the traditional “single issue” approach toward holistic approaches that consider multiple systemic challenges at once. These include access to technology, market systems development, regulatory frameworks, finance and power asymmetries.

We will continue to generate data and knowledge on the key vulnerabilities and adaptation priorities for critical global hotspots where dependency on aquatic resources and ecosystems is high. We will work in close collaboration and dialogue with advanced research institutions, national and international policymakers, small-scale fishers, farmers and community representatives, civil society groups, businesses and social entrepreneurs. Together, we will identify, design and evaluate interventions and innovation opportunities where aquatic foods play a key role in putting food systems on a low emissions pathway.

We will also employ resilient market systems development approaches to ensure that vulnerable communities that depend on fisheries and aquaculture are not only able to withstand shocks and cope with the next climate risk, but are also able to make critical investments and build relationships instrumental to their success. Research will focus on improving understanding of how these communities can attain and enhance their long-term resilience to climate change and achieve economic prosperity without compromising the ecological integrity of aquatic ecosystems and resources.

Transitioning to climate resilient aquatic food systems requires significant investments in research and innovations that can help reduce greenhouse gas emissions, minimize climate risk and enhance long-term resilience in aquatic food systems. In particular, small-scale fisheries and aquaculture are characterized by a chronic finance gap, while access to the limited finance available is challenging for those who need it the most. Therefore, research will focus on identifying potential climate finance options from both public (e.g. fiscal allocations) and private (e.g. impact investing) sources. It will also support local communities that depend on aquatic food systems to increase their knowledge, understanding and capacities to access different sources of climate finance.

At the global level, we will work with partners to generate evidence on the role of sustainable aquatic food systems in attaining greater synergy between human and ocean health, and ensure their contribution is captured and reflected in critical climate policies, such as the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) outcome documents, which have persistently failed to recognize the contribution of “healthy and sustainable diets” as a low emission pathway (Gralak et al. 2020).

One CGIAR partners

CCAFS, IWMI

Research partners

UBC, IIED, NOC (UK)

Policy and advocacy partners

ICCCAD, FAO

IMPACT AREA 2:

SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC INCLUSION

Strategic research objective 2

To generate compelling scientific evidence that persuades critical decision-makers and market actors—at all levels—to implement inclusive policies and investments in aquatic food systems for shared prosperity and well-being.

Over 90 percent of food producers are small-scale, and they dominate maritime employment. They include significant populations of full- and part-time fishers and fish farmers on the world’s agriculturally productive deltas and floodplains. These producers support highly dispersed networks of small-scale aquatic food processors and traders, who in turn support the food and nutrition security of billions of the coastal, riparian and urban poor, including those not well connected to global and commercial food markets. In many lowincome communities, consumer access to healthy foods is difficult and prohibitively expensive (Global Nutrition Report 2020).

The continued functioning of aquatic food systems depends on two factors: (1) maintaining access to “blue space” for millions of smallscale and commercial actors, and (2) maintaining the quality of the aquatic and marine environment that supports their livelihoods. Research is needed on the best ways to maintain or restore access to productive blue spaces by Indigenous Peoples, traditional fishing communities and new entrants in search of viable livelihoods.

Improvements in the livelihoods and well-being of women and men engaged in the aquatic food sector and in their incentives to participate in critical governance processes are key. These depend on the existence of a supportive and enabling policy environment and investment climate. There are several promising initiatives to build upon, such as the Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication (SSF Guidelines), led by FAO and widely endorsed by fisherfolk organizations. Various other fisheries and aquaculture stewardship initiatives encourage sustainability and equity and the emergent blue economy. Yet, most of these policy initiatives are in the early stages. Early lessons from transition processes toward sustainability require further research on effective strategies that support gender, youth and social inclusion, as well as shared prosperity and well-being for all.

One CGIAR impact themes

Nutrition and Food Security

Food system sustainability indicators:

Ecosystem Stability • Ecosystem Services • Conservation and Sustainable Use of Biodiversity • Resource Efficiency • Reduction in Food Loss and Waste • Climate Change Mitigation • Resilience

SDGs

Leave no one behind with an inclusive and people-centered blue economy

Covering more than 70 percent of the surface of our planet, the ocean and seas provide half of the world’s oxygen, sequester carbon dioxide and serve as home to 80 percent of life on earth. Globally, the value of key ocean assets has been estimated at USD 24 trillion and the value of derived services at between USD 1.5 trillion and 6 trillion per year (Österblom et al. 2020).

Together, the ocean, seas and marine resources provide nutritious food and support whole communities and millions of livelihoods around the world. Yet, we collect only 2 percent of our food from the ocean. We have already started to link our traditional research work on fisheries and aquaculture with the blue economy and the ocean space. This will help advance understanding of the global human-ocean system across social and natural sciences, as well as different sectors of the economy (Cohen et al. 2019; Bennett et al. 2019). Our research with partners shows that current access to ocean benefits and resources, as well as exposure to harms, is distributed inequitably (Österblom 2020).

This results in negative effects that vary across contexts and communities. They impact the environment and human health and limit financial opportunities. They lead to loss of livelihoods and create challenges to food security and nutrition for vulnerable groups. Decision-makers lack the data and information necessary to implement equitable solutions that do not further disadvantage the marginalized, the disempowered and those otherwise unable to equally access or benefit from the ocean and the emerging blue economy.

We are already connecting with and mobilizing an international and transdisciplinary network of researchers to generate and integrate evidence with human-centered tools, perspectives and narratives. This will bridge the gap between policymakers and public and private sector investors on the one hand and the people most dependent on aquatic food systems on the other. Our findings will continue to inform policies, institutions and investment decisions that lead to system-level transformations. The purpose of these transformations is to fully recognize the diverse uses and users of aquatic environments, their contributions to society and the interrelated issues of climate change, One Health, human rights, justice and equity, gender and social inclusion, and shared prosperity.

At the global level, we will include the interests and priorities of small-scale fishers and fish farmers in the ocean governance agenda. We will also expand the conversation beyond conservation and economic growth to consider the ocean as an important source of food and human well-being for generations to come. To accomplish both of these goals, we will actively leverage our scientific expertise and evidence, convening power, international policy-research network and links with the HighLevel Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy.

One CGIAR partners

IFPRI, IWMI

Research partners

Nippon Foundation Nereus Program,

JCU, TBTI Network,

University of Lancaster,

ANCORS Wollongong University,

Center for Sustaining Seafood, UW

Policy and advocacy partners

FAO, ICSF, NACA, High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy, Friends of Ocean Action, Freshwater Alliance

Improve the availability, accessibility and affordability of aquatic foods for all

Aquatic foods are highly traded internationally (Asche et al. 2015). But in most of the geographies where we work, value chains that deliver food to domestic consumers are far more important in terms of volumes of food produced and consumed, and numbers of people employed (Bush et al. 2019). Historically, most research on aquatic foods has been focused on fishers and farmers. This overlooks the importance of actors in the “hidden middle” of the supply chain who provide essential services to producers and enable the flow of affordable aquatic foods to consumers (Tezzo et al. 2020).

Many aquatic food value chains in our focus geographies are undergoing rapid growth and technological change in response to drivers such as urbanization and associated shifts in demand. At present, these chains are comprised mainly of small and medium enterprises. Value chains organized in this way tend to be inclusive in the sense that barriers to entry for smaller actors are relatively low. However, the fragmented nature of such chains makes them hard to regulate. This characteristic makes it difficult to institute environmental, food safety or labor standards, and traceability (Belton et al. 2020). The complexity and rapidly changing nature of aquatic food value chains means that their significance and characteristics are often poorly understood, and little is known about their resilience to systemic shocks, such as climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Drawing on the expertise of WorldFish and its partners, research in this area consists of rigorous interdisciplinary mixed-methods assessments of the structure, conduct and performance of aquatic food supply chains. The key is to understand how value chains operate in terms of economic organization, governance, power dynamics, technical and environmental performance, and contributions to human well-being.

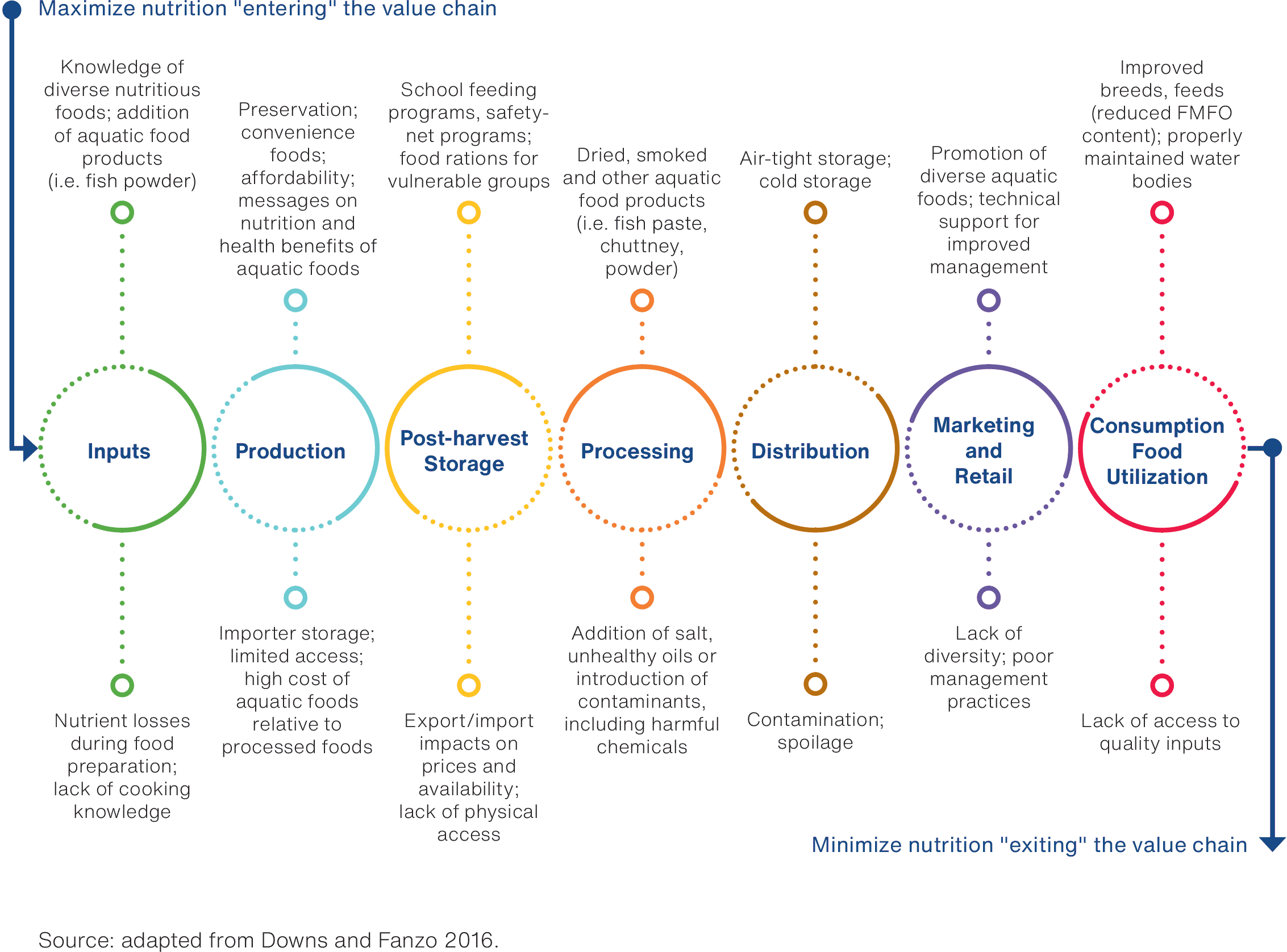

Deepening our understanding of these areas can provide evidence-based recommendations for policy and market actor interventions that support more equitable, inclusive and sustainable outcomes for all. More importantly, knowledge of value chain dynamics can inform actions and innovations by different stakeholders to retain and increase nutrition along the entire aquatic food value chain (Fanzo and Downs 2017) as depicted in Figure 5.

Digital innovations play an increasingly important role in shaping the behavior of actors in aquatic food supply chains and in developing new modes of value chain governance. These innovations are altering the nature of and possibilities for value chain research. A “Blue” Big Data Revolution and growing AgriTech investments can support the delivery of a flexible, intelligent and transparent (FIT) food system. A FIT datadriven food system can optimize the way in which aquatic foods are harvested, farmed, traced, processed, traded, stored, transported, marketed, distributed and made accessible and safe for human consumption. We have already developed a number of award-winning pilot FIT type projects in small-scale fisheries, aquatic animal health, finfish genetics and value chain analysis of aquatic food markets. They make use of big data, artificial intelligence, remote sensing, cloud computing and machine learning and enable us to generate more precise research insights that are representative at larger scales.

One CGIAR partners

IFPRI, CIAT

Research partners

MSU, University of Manitoba, WUR, USAID, Innovation Lab for Fish, University of Stirling

Policy and advocacy partners

USAID, FAO, IFAD

Support sustainable livelihoods, decent work and well-being

A food system is sustainable if its producers, processors, distributors and consumers have adequate income, decent work and dignified, fulfilled lives. Efforts have been made to foster more sustainable supplies of aquatic foods through regulation aimed at improving resource management and productivity and reducing the negative environmental impacts (Bush et al. 2018). However, these efforts have overlooked the social dimensions of sustainability, including well-being, human rights and gender equality. This unbalanced understanding of the relationship between social and environmental sustainability has begun to shift as labor conditions in the aquatic food system have come under closer scrutiny, following exposés highlighting labor abuses in fisheries and aquaculture supply chains (Marschke and Vandergeest 2016).

More positively, well-being has gained prominence as an alternative means of conceptualizing and assessing progress against human development goals, in recognition of the limitations of using economic growth as an indicator of social progress (Gough and McGregor 2007; Stiglitz et al. 2009). Following this lead, fisheries researchers have adopted well-being as a means of accounting for the diverse contributions that fisheries make to the livelihoods of fishers and fishing communities (Weeratunge et al. 2013). Our work in this area seeks to foster sustainable livelihoods that are founded on decent work and contribute to enhanced social well-being in all its dimensions: relational, subjective and material. The scope of our research on fisheries and aquaculture is expanding to pay closer and more explicit attention to workers and working conditions in aquatic value chains. This will create public awareness of any problems encountered to leverage support for effective policy and public and private regulations.

Drawing on conceptualizations of well-being, we will also examine the human dimensions of aquatic livelihoods more closely. This will help account for the diverse meanings and associations experienced by people participating in these activities (e.g. sense of belonging, satisfaction or exclusion), and how these vary according to the identity of those involved (e.g. women and men, migrants and citizens), the roles they perform and their degree of agency and control over resources.

Improving the lives of men and women engaged in aquatic foods sector does not just stop with them; it translates into benefits for their children, families, communities and the nations to which they belong. Research insights here are critical entry points for building more satisfying, equitable and empowered livelihoods, and measuring the outcomes and impact of research and innovation in a more multidimensional and people-centered manner.

One CGIAR partners

IFPRI, IWMI, CIFOR, IITA

Research partners

School of International Development, University of East Anglia, Cornell University, MARE, University of Amsterdam

Policy and advocacy partners

USAID, FAO, IFAD

IMPACT AREA 3:

NUTRITION AND HUMAN HEALTH

Strategic research objective 3

To advance and increase scientific knowledge and public awareness and understanding of the nutrition, safety and health benefits of aquatic foods.

Combating malnutrition (in all its forms) and diet-related noncommunicable diseases represents one of the greatest global health challenges. Policymakers, businesses and civil society and consumers are increasingly concerned about the links between food system sustainability, nutrition and public health concerns. Solutions require joined-up responses between the scientific community and the public and private sectors. Nutrient-rich aquatic foods offer a life-changing option for the 2 billion people suffering the triple burden of malnutrition. The intake of omega-3 fatty acids from fish is associated with lower risk of cardiovascular disease and obesity. Aquatic foods present an important but largely overlooked solution.

Gaps in the quality and availability of reliable nutritional data make it difficult to determine what people consume around the world, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. With our partners in the global Blue Food Assessment, we are making progress in showcasing how the diversity of aquatic foods contributes to nutrition and public health, fuels local and national economies and plays an essential role in the shift toward sustainable, healthy food systems. Results will be released ahead of the UN Food System Summit 2021. Our aim is to galvanize ambitious new actions, innovative solutions and plans in order to maximize the benefits of aquatic foods across the entire 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

At the global level, we will continue to leverage our research results, convening power, and wide policy-research network, as well as our voice in the HLPE. This will help set, align and advocate for policies and actions that include aquatic foods in the global nutrition agenda and related policies. At the country level, our work continues to inform national dietary guidelines and recommendations on diverse, healthy and sustainable aquatic foods. It also strengthens research skills and capacities to integrate aquatic food interventions in national policies for improved health, nutrition and environmental sustainability.

One CGIAR impact themes

Nutrition and Food Security

Food system sustainability indicators:

Human Health • Food Nutrient Adequacy • Food Safety • Food Use

SDGs

Inform consumer demand for healthy and nutritious aquatic foods

Fish and many other aquatic foods are a great source of lowfat quality protein. Packed with numerous vitamins, fatty acids, minerals and micronutrients, they are essential to good nutrition and health. Many aquatic foods are an excellent source of B12, or Cobalamin, which is necessary for making DNA, creating energy in our cells, and particularly for supporting cognitive development in the first 1000 days of a child’s life. When consumed as part of a balanced diet, fish can increase the absorption of essential minerals such as iron and zinc from other foods. The head, viscera and backbones, which make up 30 to 70 percent of the fish, have the highest concentration of micronutrients, but often are the less valued and preferred parts by consumers.

Consumer preferences for fish and aquatic food vary according to a range of factors. A person’s gender, level of education and income, as well as the physical characteristics of fish and aquatic foods, knowledge and ease of cooking, appearance, taste and smell factors play a role in how willing consumers are to consume aquatic foods. The role of food environments in shaping consumer preferences, food purchasing, the quality of diets, and diet-related health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries remains understudied but is gaining increasing policy attention (Turner et al. 2018).

Research in this area and on the health and nutrition value of balanced diets that include aquatic foods will guide the development of safe, convenient and healthy aquatic food products that meet and inform consumer demand and reach those who need them the most. Our work will focus primarily on women, children in the first 1000 days of life, and adolescents who require high levels of multiple essential nutrients for good health and development. We will continue to scale a number of successful pilot innovations in Bangladesh, Cambodia and India on aquatic food products developed, marketed and distributed in partnership with development agencies, food industry actors, local governments and civil society organizations. These aquatic food products include convenient complementary foods, snacks and condiments. They are made of highly nutritious small fish and seaweed along with fish chutneys and powders to fortify the diets of women and young children suffering from malnutrition and for use in feeding programs for school children and refugees.

We will work with local actors to increase awareness on the health and nutrition benefits of aquatic foods, using successful social and behavior change communication approaches from the health sector. Our research evidence will inform supply-side interventions to (1) produce quality, healthy and sustainable aquatic food products (2) promote nutrition-sensitive aquaculture and polyculture systems, and (3) prevent the loss of aquatic food quantity and quality through innovative loss and waste technologies and improved practices as well as integrated farming systems with fish, rice and vegetables for balanced, nutritious and sustainable diets.

One CGIAR partners

IFPRI; CIP; AfricaRice, IRRI, IWMI

Research partners

WUR, University of Ibadan, BFRF, BFRI, USAID Food Safety Innovation Lab, Cornell University

Policy and advocacy partners

USAID, BMGF, DFID, GAIN, World Bank, African Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, ACIAR, national and regional governments

Ensure aquatic foods are safe and healthy for human consumption

The safety of food is an important health, social and economic issue. The impact of unsafe food in low- and middle-income economies costs about USD 110 billion in medical expenses and lost productivity each year (Jaffee et al. 2019). Contaminated food causes foodborne diseases, and these occur at all stages of the production, delivery and consumption chain. They can result from several forms of environmental contamination, including water, soil or air pollution, as well as unsafe food storage and processing.

Our research to ensure the safety of aquatic foods for human consumption is governed by the principles of One Health. They recognize that human and animal health are interdependent and bound to the health of the ecosystems they exist in, as the COVID-19 pandemic has made strikingly clear. We will continue to carry out scientific risk assessments and related risk management guidelines and communications for all stakeholders in aquaculture and fisheries, including producers, processors, traders, handlers, consumers and policymakers. The goal is to improve their knowledge and capacities to prevent and control foodborne diseases and increase the safety of aquatic foods through improved standards, policies and investments.

We will engage across sectors and disciplines from aquaculture and fisheries production and value chains, public health, environmental health, and animal health and welfare. We recognize that risk and disease pathways require complex interactions with many partners having different knowledge and experience than we have. In our research, we will prioritize the needs of women, people in the informal sector, and marginalized communities.

In terms of animal health, we will build upon our groundbreaking research work on fish health and antimicrobial resistance to assess the health of both farmed and wild harvested animals and plants, and the One Health implications of increasing aquaculture production and productivity. In partnership with social innovators and the private sector, we will continue to scale up innovative epidemiological tools, such as our award-winning Lab-in-a-backpack. Powered by big data and AgriTech, it is set to revolutionize control of disease outbreaks in fish farming.

One CGIAR partners

One CGIAR AMR Hub: ILRI, IFPRI and IWMI; CRP on A4NH

Research partners

CEFAS, LSHTM, USAID Innovation Lab for Fish, Royal Veterinary College, University of Exeter, ICARS, Norwegian Veterinary Institute, Stockholm Resilience Centre, University of Queensland

Policy and advocacy partners

The Fleming Fund, Ending Pandemics, INFOFISH, NACA, regional networks in Africa, FAO, WHO

Prioritize nutrition and health for vulnerable and marginalized people

Multiple essential nutrients from aquatic foods (Bogard 2015) are critical to human health and to cognitive development in children in their first 1000 days. Yet research shows that they are slipping through the hands of millions of malnourished people living in coastal communities (Hicks et al. 2019a). Aquatic foods are currently caught off the West African coast, the Pacific and the Caribbean. This food source is sufficient to meet the nutritional needs of the people living within 100 km of the sea, especially those who suffer from high levels of deficiency in zinc, iron and vitamin A.

Building on this work, research in this area will seek to unravel the complex picture of international and illegal fishing, seafood trade, and cultural practices and norms that stand in the way of good nutrition and health for millions of people suffering from malnourishment and noncommunicable diseases in lowand middle income countries. Our insights will inform key shifts in policies, investments and sustainable development interventions. These are required to prioritize nutrition and health for marginalized women, men and children who live in extreme poverty and are internally or externally displaced by conflict, violence or the impacts of climate change.

Research will focus on developing aquatic food solutions to mitigate the dire impacts of COVID-19 on the nutrition and health of this population group. We will continue to work closely with private and public sector actors to ensure affordable and culturally acceptable aquatic foods and related nutrition information are included in food assistance programs, social protection schemes, humanitarian emergency responses, school feeding programs, and maternal and child health programs. Research will generate and evaluate evidence of outcomes to critically assess interventions, provide lessons and insights on aquatic food pathways and influence policies and investments for securing nutrition and health for vulnerable and marginalized people in low- and middle-income countries.

One CGIAR partners

IFPRI, CIP, IWMI

Research partners

WUR, University of Copenhagen, IMR

Policy and advocacy partners

WFP, FAO, UNICEF, SUN, USAID, USDA, NORAD,national and regional governments

INCREASING THE

SPEED OF INNOVATION

Research alone cannot provide people with more and better food, improve environmental sustainability or reduce climate risk. Success in our world depends on ensuring research is relevant, credible, legitimate and effective (ISDC 2020). Research must be open and accessible to everyone so that it guides, inspires and builds knowledge and capacities for transformative action from actors and stakeholders at all levels of the food system. Moreover, the speed of innovation in food, land and water systems needs to accelerate to meet global challenges associated with the increasing threat of climate change and environmental degradation, as well as social exclusion and poverty.

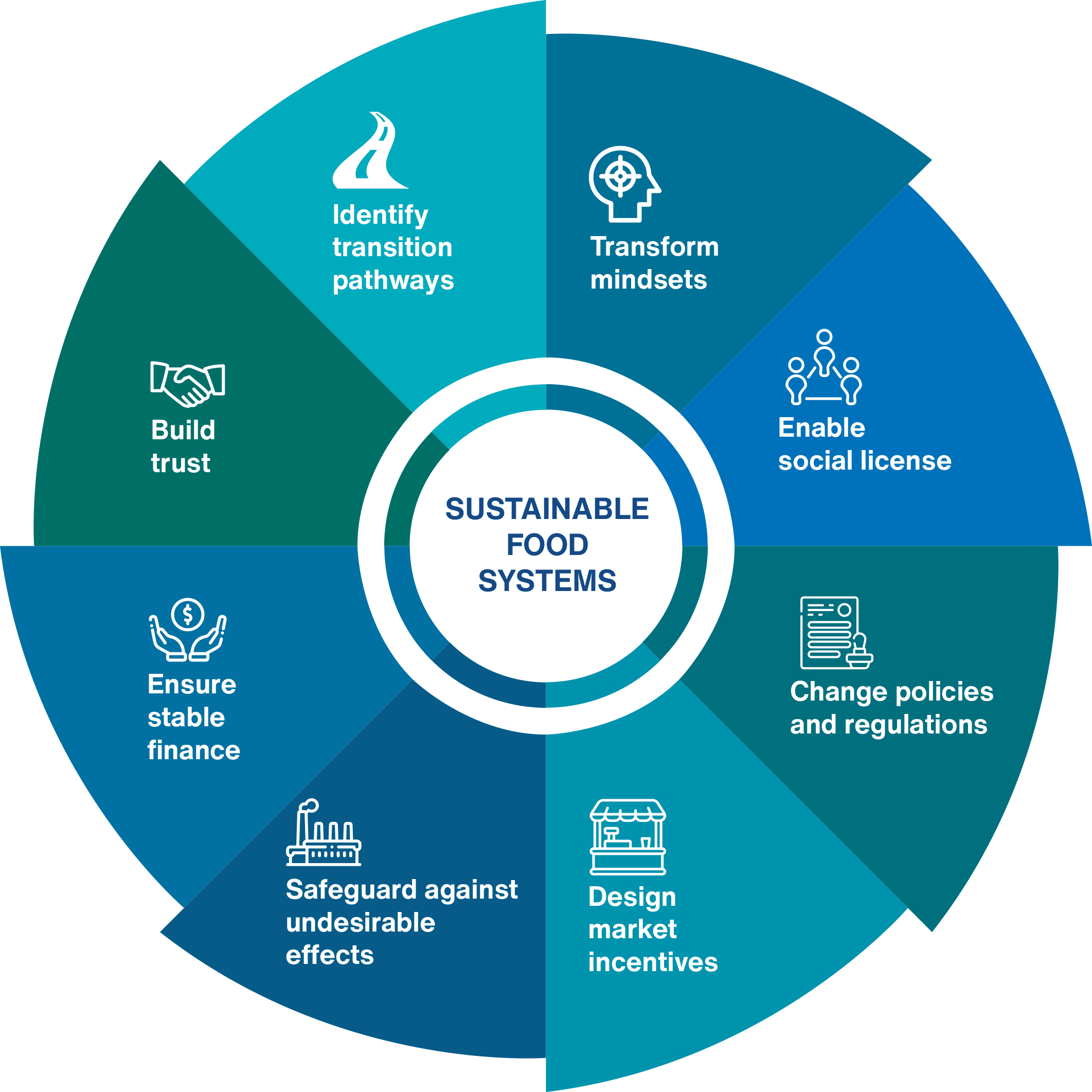

We recognize that transformative change requires our work to be situated within an innovation ecosystem of partners, stakeholders, networks, assets and institutions to turn research into demand-driven products, services and solutions at scale. Examining the deep structural factors and impact pathways that lead to system transformations is critical, and it starts with four keys areas: (1) the worldviews and values of actors that give the system its orientation, (2) the social structures and institutions that manage system feedbacks and parameters (Ives 2020; Abson et al. 2017), (3) the forces that help or hinder change, and (4) investments in the means to accelerate system transformation at different levels (Herrero et al. 2020). We must embrace new ways of thinking about research and innovation, as well as innovative ways of cocreating, learning, engaging and collaborating with diverse partners and stakeholders to deliver concrete and measurable impacts at scale.

01

Identify transition pathways

This requires rigorous evaluation of alternative technology, policy, societal and economic development scenarios, the roles aquatic foods play in them, and the actions needed to support movement toward food systems sustainability. And it is necessary for achieving multiple benefits across the five SDG-focused grand challenges outlined by One CGIAR.

02

Transform mindsets

Development of effective research knowledge or technology is no guarantee for social acceptance due to deeply engrained biological, psychological and cultural relationships to food. Engaging different food system actors will expand learning and understanding on aquatic foods and their role in food system transformation toward healthy and sustainable diets.

03

Enable social license and stakeholder dialogue

Investment in novel lab-grown fish or plant-based fish substitutes, genetically improved or new farmed aquatic food species and related production systems is tied to social license, technology acceptability, and know-how to facilitate uptake. Extensive public dialogue and consideration for responsible innovation are key here to ensure that public knowledge and opinion—particularly for food systems actions with less education in low-income countries—is guided by the best science available.

04

Change policies and regulations toward food systems sustainability

Expectations about future policies are essential for both public and private investments in technological and system change. Although there could be public acceptance or a call for change, existing rules and norms can block uptake of new ideas that foster food systems sustainability. Research on social equity and governance can identify the means to ensure policies and regulations are guided by both public opinion and expert science.

05

Design market incentives

Transformational innovations are often context and technology specific, and barriers to scaling and uptake differ widely in different markets. Innovation incubators and accelerators often play a key role in bringing novel solutions to market. Research on critical market incentives and potential instruments is critical to support food system transformation. These include tax breaks, patents, temporary monopolies or the design and financing of innovation hubs and incubators in the aquatic food sector.

06

Ensure stable finance

Technologies associated with aquatic foods often involve a physical product that is subject to production seasonality and complex regulations. These pose diffusion challenges because the financial environment does not reward the “fail fast and restart/iterate” model. Moreover, research and development cycles are quite long for a broad range of technologies, such as genetically improved finfish. Coupled with AgriTech opportunities, creative investment solutions in partnership with public and private sectors are critical to ensuring appropriate and longer-term finance for research and innovation as a prerequisite to food system transformation.

07

Build trust among food sector stakeholders

Transformation requires consensus and support from many actors within the food system that are connected through complex economics and social networks. They include fishers, farmers, consumers food companies, civil society actors and government. Creating trust is central to build shared values and secure broad-based collaboration on different technology choices and food system outcomes, such as sustainability, social inclusion, justice and equity, environmental impact and economic benefits.

08

Safeguard against undesirable effects

Sometimes, the unintended consequences of a new policy or investment framework designed to harness the potential of new knowledge or technology can be overlooked, especially where public acceptance and the regulatory landscape remains to be determined. Research on gender, human rights, social exclusion and vulnerability, as well as on the environmental impacts of aquatic food production, can help shed light on these issues, ensure impacts are thoroughly evaluated, and provide recommendations that safeguard against undesirable effects on the poorest and most vulnerable communities who depend on aquatic resources and related value chains.

This transformative action framework builds on firm foundations of our research work with partners in fisheries and aquaculture as main aquatic food production systems, as well as our genetics gains, digital technologies and social and policy research. It complements the wider One CGIAR efforts to develop a more ambitious transformative research agenda that links food, land and water systems together and brings about measurable positive change across all five One CGIAR challenges and areas of impact.

Increasing the speed of innovation toward sustainable aquatic food systems.

Source: adapted from Herrero et al. 2020.

This transformative action framework builds on firm foundations of our research work with partners in fisheries and aquaculture as main aquatic food production systems, as well as our genetics gains, digital technologies and social and policy research. It complements the wider One CGIAR efforts to develop a more ambitious transformative research agenda that links food, land and water systems together and brings about measurable positive change across all five One CGIAR challenges and areas of impact.

ACCELERATING TRANSFORMATION

WITH AQUATIC FOODS FUTURES

Prospects and Challenges of Fish for Food Security in Africa and Fish to 2050 in the ASEAN Region are examples of two landmark studies generating important foresights and people-centered scenarios into aquatic food futures to inform policies and investment decisions in low- and middleincome countries. We will build on these foundations to generate new systematic, interdisciplinary and holistic studies of social and technological advancement, and other environmental trends to help set the direction for aquatic food futures of shared prosperity and inclusive growth.

An Aquatic Food Futures Lab to spark innovation and social change

We will create an Aquatic Food Futures Lab to bring together a multidisciplinary team of researchers and innovators, policymakers, social entrepreneurs, business strategists, philanthropists, technology enthusiasts and creative communicators who all share a deep passion for building a more sustainable, healthy, equitable and humane future with aquatic foods.

We will enable greater understanding of the socioeconomic and environmental costs and benefits for policy and investment decisions in aquatic foods at various food system levels. In addition, we will provide national governments and development actors with concrete scenarios for making informed choices. Powered by an inclusive digital platform, the Aquatic Food Futures Lab will have the features of a networked innovation ecosystem, with informal softer structures that support learning and crossfertilization of ideas across teams and partners, engaging women, young people and marginalized groups in particular.

To shape the social change agenda and spark transformative change, we will translate the scientific findings of our futures research into compelling stories across many mediums: pages, stages, packages, farms, and even chefs and dining room tables. Transforming valuable foresight into actionable insight, the lab will be a catalyst for co-created innovations in markets, policies and institutions. These innovations will improve evidence-based decisions, strengthen the skills, knowledge and capacities in aquatic foods research and value chains, and increase investments in sustainable and inclusive aquatic food solutions.

Fish for Africa Innovation Hub

In Africa, fish has unfortunately often been overlooked and underestimated in securing food, nutrition and health outcomes, especially for malnourished women and children. Aquaculture and fish value chains support the livelihoods of an estimated 12.3 million people across the continent. In sub-Saharan Africa, where extreme poverty is on the rise and projected to hit 416 million by 2030, the vast inland waters and coastlines are home to a small but rapidly growing aquaculture sector. Aquatic food systems and value chains hold great promise for addressing food security and nutrition needs in the region, while boosting progress on gender equality and enabling sustainable economic development in the face of climate change.

Work is already underway to establish a Fish for Africa Innovation Hub. We are building on our success with partners in transforming Egypt’s aquaculture sector over the past 20 years, and there is growing continental demand for data, knowledge, training capacity development, new jobs, businesses and entrepreneurship opportunities in both fisheries and aquaculture. Designed as a public-private partnership, the hub aims to spark and scale co-created scientific, policy and market innovations. These will catalyze transformational change in the continent’s food systems and create inclusive opportunities in the emerging blue economy, particularly for women and young people.

A Global Index on Aquatic Foods and flagship Fish for Africa Innovation Hub

Reflecting data and insights across all elements of food systems sustainability, we will work with One CGIAR and other partners to establish a Global Index of Aquatic Food Systems, to be published every 2 years. This will be a primary scientific research and communications output designed to fill existing gaps in knowledge and understanding of aquatic food systems. It will provide policymakers, public and private sector investors, civil society actors, media, the general public, and the people and communities who depend on sustainable fisheries and aquaculture with an objective and comprehensive view of aquatic foods systems in low- and middle-income countries, including policy and investment briefs on specific issues of interest.

To engage a diverse spectrum of audiences and stakeholders, a global public information and digital communications campaign will accompany the index, publication and related policy and investment briefs. The global report will primarily target policymakers and decision-makers. But it will also seek to be agenda setting and relevant to experts, academia, students, the media and the general public to ensure our research insights are translated into broad transformative action on aquatic food systems.

FROM RESEARCH

TO OUTCOMES AND IMPACT

Our institutional strategy for research on aquatic food systems to 2030 provides a guiding framework for exploring and identifying sustainable food systems transformation approaches and scenarios at the intersection of research, technology, policies, markets and social innovations across different disciplines and sectors.

The framework provides the conceptual underpinnings and operational approaches that guide how programmatic decisions will be made based on a clear intent to achieve specific results. These include how new and existing research programs and projects on aquatic foods systems will learn and adapt to retain their relevance and focus in making the shift toward aquatic food system research and innovation. The framework applies to all future research programs, projects and engagement by WorldFish with partners within One CGIAR and the wider scientific community. The strategy will be accompanied by a strategic results framework that is aligned with the One CGIAR Research Strategy 2020–2030. It will identify transformation pathways, from research outputs and outcomes all the way to impacts, that take into account the four dimensions of natural, produced, human and social capital in food systems, from production through to consumption (Kumar 2010).

An integrated set of indicators will assess the collective impact of the research activities. These indicators will help to evaluate and track progress toward the sustainability of diets and food systems, which is a critical step in building national transformative pathways (Chaudhary et al. 2018). The research outputs and outcomes are designed to address the five One CGIAR global challenges and the social, economic and environmental dimensions of the 2030 SDGs. The output and outcome-level indicators will serve as yardsticks for monitoring results, evaluation and learning to enable adaptive management, innovation and effective partnerships. This approach will allow us to identify synergies that can result in win-win outcomes while remaining vigilant and transparent about difficult trade-offs

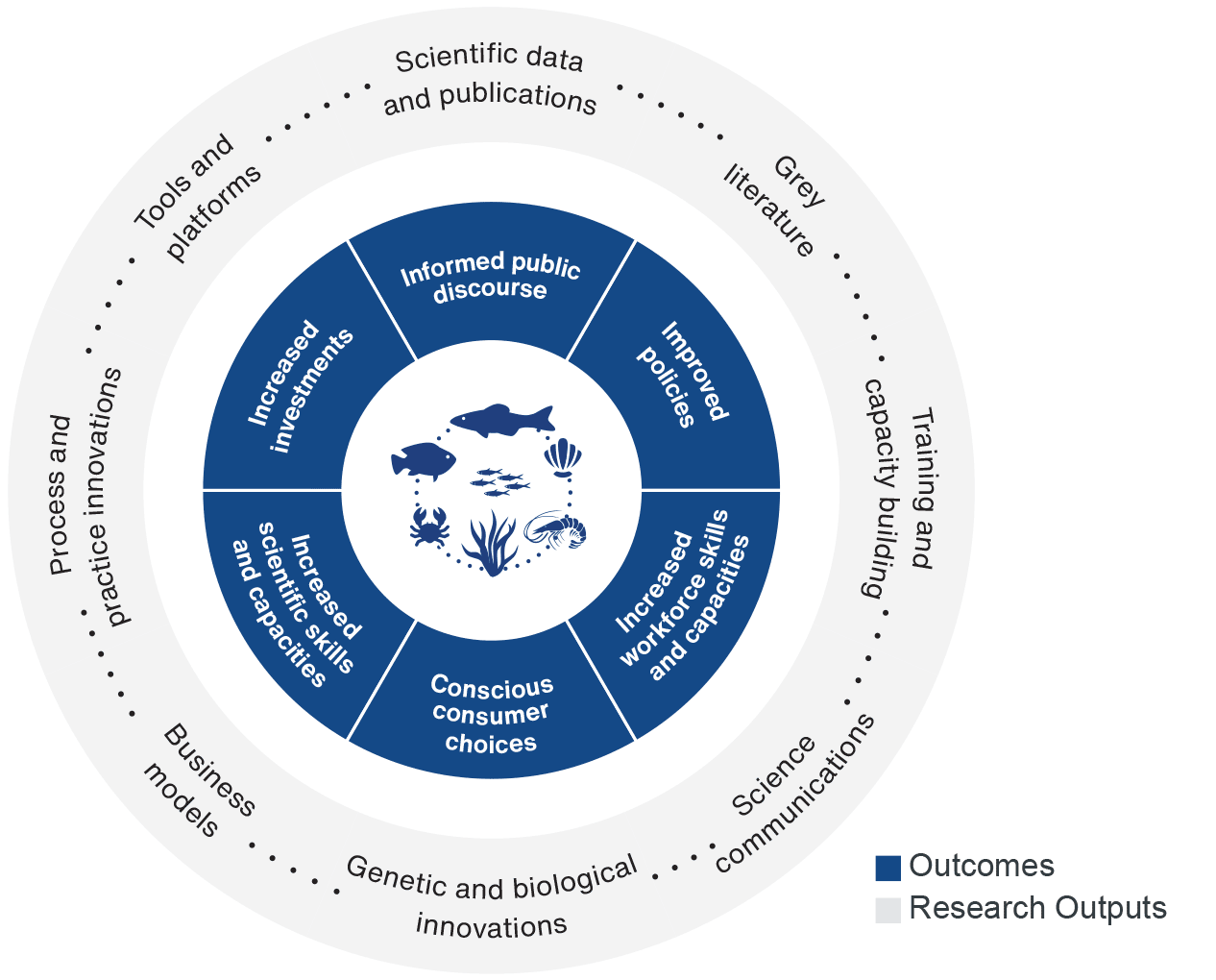

The main outputs of our research work fall into eight main categories: (1) scientific data and publications, (2) tools and platforms, (3) genetic or biological innovations, (4) grey literature, (5) process and practice innovations, (6) training and capacity building, (7) business models, and (8) science communication products. We will track and evaluate six types of intermediate outcomes as critical pathways to our three broad areas of impact described earlier:

1

Informed public discourse

Research on aquatic foods systems leads to increased awareness and shifts in attitudes, perceptions and norms at different levels.

2

Improved policies

Research on aquatic food systems results in positive changes in formal and informal policies at local, country and international levels, as well as strengthened institutions and inclusive planning and decision-making processes for different actors at all levels.

3

Increased investments

Research on aquatic food systems leads to positive changes in investment decisions that prioritize the needs of women, men and young people who depend on aquatic foods for food, nutrition, livelihoods and well-being.

4

Increased scientific skills and capacities

Research on aquatic foods systems strengthens individual and organizational capacities for science of the highest quality in low- and middle-income countries.

5

Increased workforce skills and capacities

Research on aquatic foods systems strengthens individual and organizational capacities for business, entrepreneurship and other income-generating activities.

6

Conscious consumer choices

Research on aquatic foods systems shifts demand for aquatic foods in line with customer trends and preference for improved nutrition and environmental sustainability.

Our pioneering gender-transformative approaches will be integrated at all levels into all our research programs and projects. This will ensure equitable and socially inclusive outcomes for women, men, young people and marginalized communities in our focus countries in Africa, Asia, the Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean.

RESULTS-BASED MANAGEMENT FOR LEARNING,

ACCOUNTABILITY AND IMPACT

WorldFish will improve integrated program planning and resource allocation that focus on performance and management effectiveness. To accomplish this, we will continue to build on the achievements of the results-based management (RBM) approaches and the award-winning monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) system introduced in 2016 through implementation of the CGIAR Research Program on Fish Agri-Food Systems (FISH). This supported a positive shift in our organizational culture and in the way research programs and projects are designed, and activities and deliverables are monitored, implemented and reported, with emphasis on results and impacts.

We will continue to mainstream RBM in five main areas, as shown below.

STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT

This is focused on the vision and strategic framework guiding the adoption of RBM as a management strategy. It includes having a change management plan and an appropriate accountability framework for RBM implementation.

OPERATIONAL MANAGEMENT

Here, the focus is on what the organization does in terms of strategic planning, programming and resource management, including human and financial resources, as well as physical and virtual assets.

ACCOUNTABILITY AND LEARNING MANAGEMENT

In this area, the focus is on monitoring, evaluation and reporting, and on a data and information management system, as well as knowledge sharing and learning.

CHANGE MANAGEMENT

This area focuses on a culture of results through internalization and capacity development, leadership and using results as part of developing a learning organization.

RESPONSIBILITY MANAGEMENT

This area focuses on partnerships to attain outcomes and collective impact that will facilitate collective accountability, both vertical and horizontal, across WorldFish and with core implementing partners.

Progress will be monitored and evaluated through quarterly and annual reviews and tracked through an institutional strategy scorecard and a results framework for all research programs and projects on aquatic food systems.

The following RBM principles will be applied in all five areas of RBM:

- vision and clarity of the desired end product or impact

- causal links in a hierarchy of results (inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes, impact) based on a theory of how change happens, yet with the understanding that all hypotheses are subject to margins of error

- systems operations going beyond the linear, causal logic of closed systems, considering context, espousing “equifinality” (the principle that, in open systems, a given end state can be reached by many potential means or trajectories) and addressing risks to and conditions for success in achieving higher-level results

- performance measurement for transparency, consensus-building based on a common perspective on results, and accountability

- performance monitoring for single-loop learning

- evaluation for double-loop learning and direction-setting.

These principles echo the imperatives set out in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the One CGIAR Research Quality Framework. They include systems operations, integrated and interdependent ways of working for collective outcomes and impact, as well as horizontal and vertical accountability and the development of a dynamic and resilient learning organization.

Our intention is to continue using RBM approaches in order to accomplish the following:

- Demonstrate the effectiveness of the R4D investments in aquatic food systems.

- Increase accountability by helping shift the focus of planning, budgeting, reporting and oversight from how things are done to what is accomplished and looking at the return of the investments.

- Mainstream learning, both from success and failure, into the program management cycle to enhance an adaptive management and improved performances.

- Build ownership at all levels of the implementation of the program with national and international partners from projects to countries where the strategy will be implemented.

- Support advocacy, communications and resource mobilization by generating the required scientific data and evidence to support the sustainable transformation of global food systems with aquatic foods.

In line with our gender equality commitments, we will ensure gender is mainstreamed and integrated into all aspects of program planning, implementation and reporting. Activities and results will be examined for their gender relevance. Both qualitative and quantitative data will be identified to measure impacts on gender equality. Annual plans of work and budget and reports will be produced and shared publicly to increase transparency, accountability and learning. Our comprehensive RBM system will be supported by the award-winning MEL platform to capture performance results in real time and at different levels, from research outputs and knowledge products to SDGs. Partners, funders and the general public will have timely access to evidence and progress against objectives.