- Conservation and fisheries management interventions can help sustain healthy aquatic ecosystems that are critical to providing food, nutrition, and employment to coastal communities in Bangladesh - but such interventions often have negative social and economic impacts.

- Incentive-based approaches, like Bangladesh’s rice compensation scheme, have the potential to mitigate these impacts.

- Fishers, fish workers, government officials, NGOs, financial institutions, and researchers, gathered in Dhaka to share knowledge and plan a way forward for incentives to support equitable coastal conservation and fisheries management.

Fish is integral to Bangladesh’s national diet and culture. Yet, most of Bangladesh’s coastal small-scale fishing communities make only marginal livelihoods from fishing. Their income source is further under threat from rising sea levels, weather disasters, environmental degradation, pollution, insecure tenure (land/fishing grounds), and lack of alternative opportunities — often resulting in further poverty and overfishing.

Bangladesh has introduced conservation measures to better manage fisheries that communities rely on, such as for restoring stocks of their most prized fish, hilsa. Notable measures include sanctuaries, seasonal closures and gear restrictions, and an innovative scheme compensating fishers for lost income by providing bags of rice and alternative income-generating assistance. However, much remains to be done. Achieving a fair, sustainable system involves a complex balancing act between conservation, fisheries management, and livelihoods. Small-scale fishers have also struggled with insufficient compensation for fishing bans.

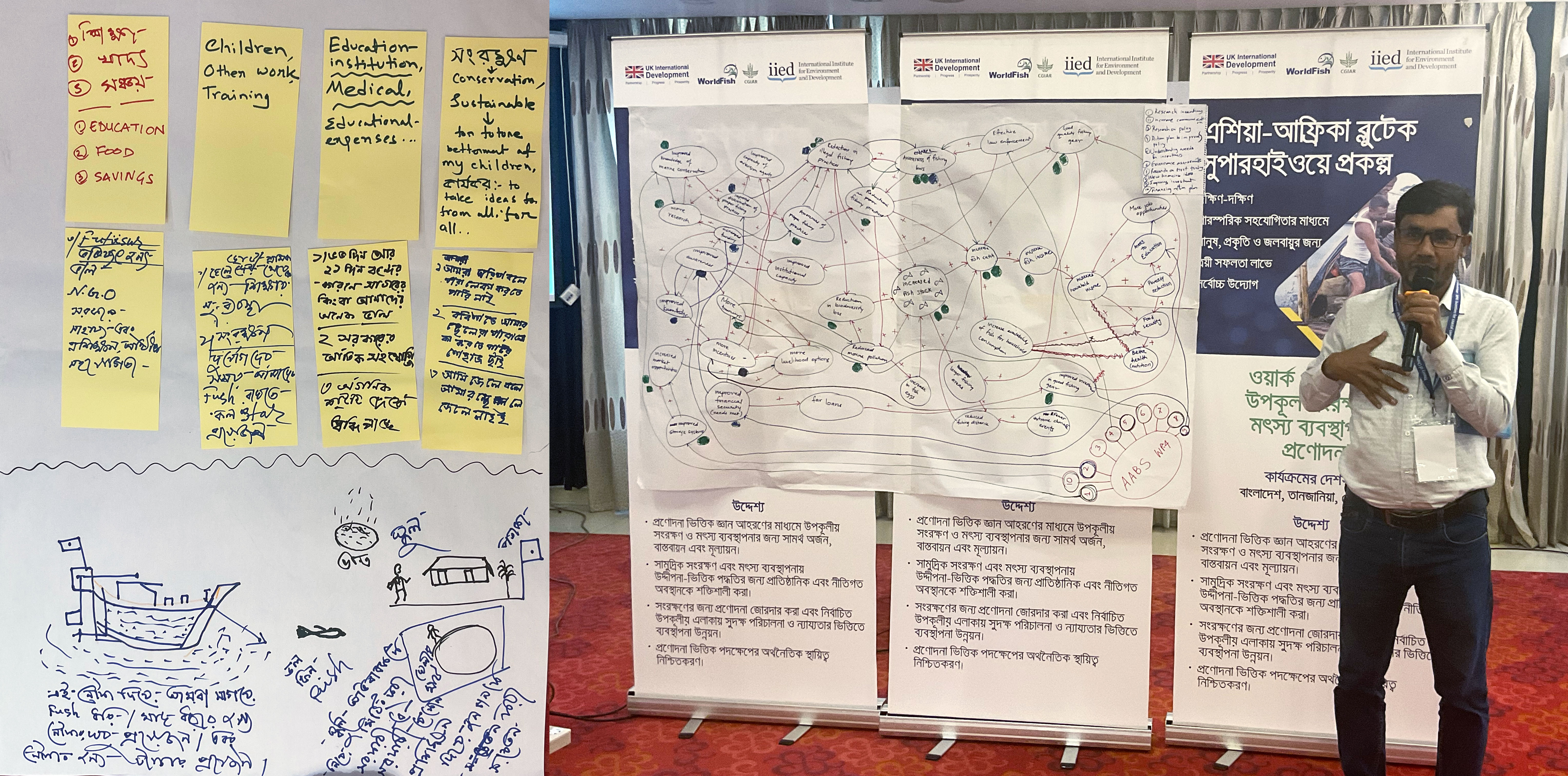

These issues were on the agenda at an Asia–Africa BlueTech Superhighway (AABS) Theory of Change workshop, held in Dhaka, from 19-21 May 2024. The workshop, aiming to develop the ToC for ‘Incentives for coastal conservation and fisheries management’ – a work package of AABS led by the International Institute of Environment and Development (IIED), gathered stakeholders to share experiences, knowledge, and visions for the potential of incentives to strengthen fisheries management and coastal conservation for people and nature.

Balancing the Needs of People and Nature

Participants from the fisheries sector, research institutes, conservation and youth NGOs, and government departments for social welfare, forestry and fisheries voiced a common goal: to ensure more fish in the sea and safeguard nature.

“We must look after the ocean because it takes care of us. It provides the fish that we need for our food and livelihoods,” said Abdul Manan, a fisher from Cox’s Bazar.

Fishers presented a clear picture of their challenges. For instance, they struggle with having enough to sell after giving the best of their catch to their creditors and affording decent healthcare and education for their children.

They also highlighted the need for better access to high-value markets, such as safely dried small fish. Although they have been trained to dry fish using organic ingredients, inputs are costly. Additionally, their weather-reliant, seasonally fluctuating work leaves them unable to access fair, low-interest loans. As a result, investing in fish-processing enterprises often leads to a debt trap.

Putting Fishers and Fish Workers at the Heart of Conservation

Dr. Samiya Selim, director of the Centre for Sustainable Development, University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh, works to support coastal communities’ resilience to extreme weather through the Vulnerability to Viability Global Partnership.

“The lack of agency is a major issue for these isolated communities. We need to ensure their voices are heard and that they are involved in shaping the decisions that impact their lives. They have little access to a social safety net when they lose a family member at sea. There not only has to be better social protection … but better awareness of how to access their entitlements or conservation incentives,” said Dr. Selim.

Registering for a fisher identity card is the starting point for accessing social protection benefits. Fisher Ula Ten from Cox’s Bazar shared that he could not access the rice compensation scheme or local training because he does not have a fisher ID card.

Dr. Selim insists fishers need easily accessible information on ID processes, social protection entitlements, and weather forecasts, and should be engaged in management and conservation.

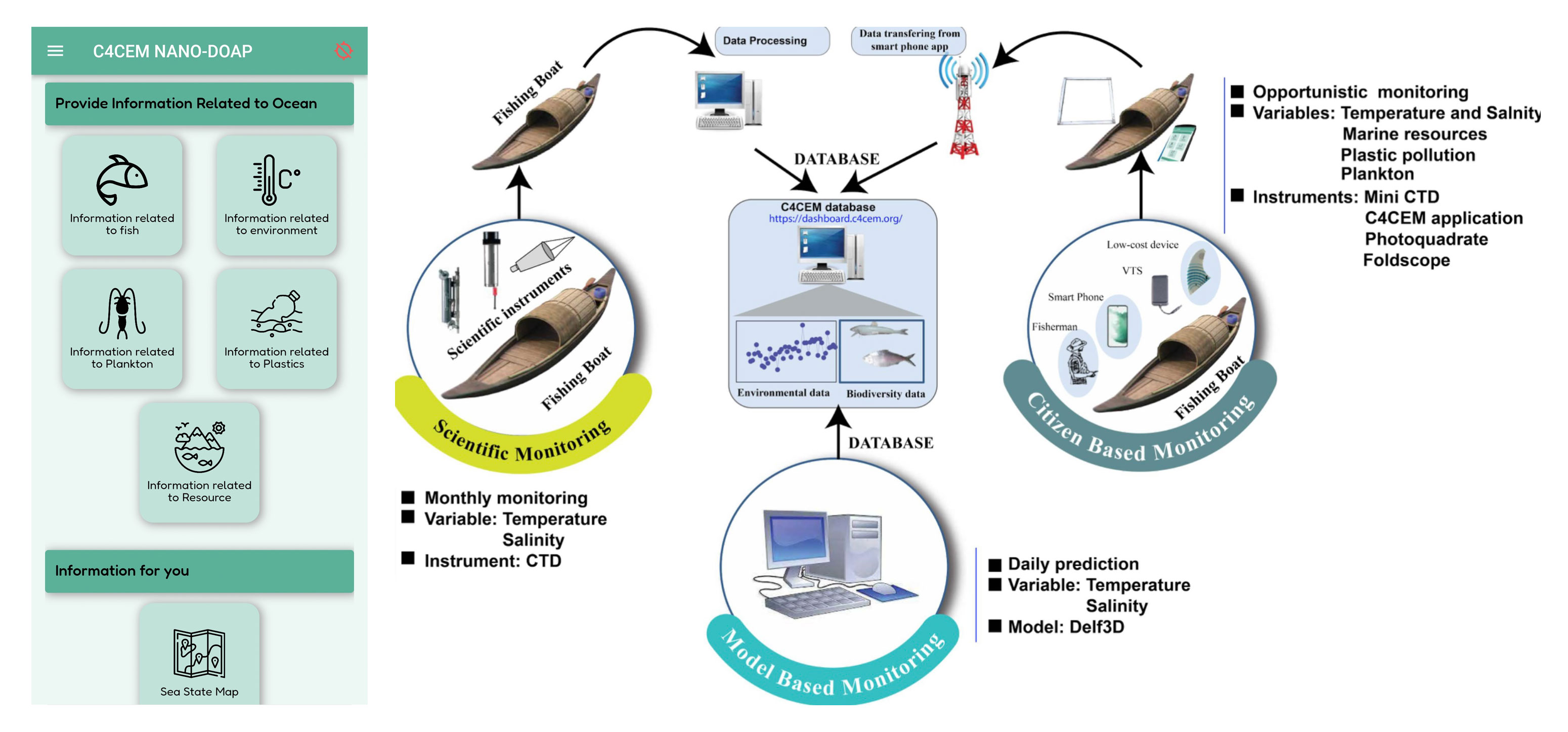

Dr. Subrata Sarker, associate professor in theDepartment of Oceanography at Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, is working with Partnership for Observation of the Global Ocean on a digital app to do this. This integrated monitoring approach was piloted in Bangladesh’s southeast coastal zone last year.

“We can adapt this interface to include information on social and legal protection, ID requirements, market linkages as well as early warning systems so that fishers can access the information they need, as well as provide data for fisheries management,” said Dr. Sarker.

Similarly, communities must be part of the solution to encourage compliance with rules. Avijit Paul from the Center for Natural Resource Studies believes time is needed to build trust between parties.

Citing one example, he said: “Community-based conservation, supported by the Bangladesh government and other development actors, has succeeded in restoring wetland biodiversity and wild fish production at a once completely degraded ecosystem, Baikka Beel, in Moulavi Bazar District about 200 km northeast of Dhaka.”

Supporting Fishing Communities to Diversify their Livelihoods

Al Mamun, from the Department of Fisheries, described the low socioeconomic conditions of fishers as a key challenge. “Limited alternative livelihoods and inadequate training are major obstacles to effective conservation”, he said. Fishers and fish workers echoed this view, pointing out that alternative livelihood projects, such as sewing and goat rearing, were not offered widely enough and lacked practical training and market access support.

“We know that providing rice is not enough to support families during the fishing ban. We need to find a way to work with social services to provide families with financial support and training to find a stable income,” said Al Mamun.

Low-interest loans would support fishing communities to develop stable income streams. According to Alamgir Kabir, microfinance director for Nowabenki Gonomukhi Foundation (NGF), banks exclude fishers due to concerns about the high-risk nature of small-scale fisheries. NGF works with the World Bank to provide affordable microcredit for fishing communities along Bangladesh’s southwest coast; this needs to be expanded to cover the entire coastline.

Fisher Abdul hopes this can become a reality. “Being at this type of workshop means we learn so much about what is possible,” he said. “We understand there are challenges and things will take time. Like others, we want more fish in the sea. We also want fair loans to invest in secure businesses, as well as training and support to help us survive hard times.”

Following the workshop, the next step is to co-design a feasible strategy with partners to address key concerns and plan actions towards much-needed solutions.

'Incentives for Coastal Conservation and Fisheries Management' is led by IIED and is one of four work packages of the AABS program implemented by WorldFish in collaboration with a host of partners.