- Rice-field pond systems integrate fish, rice, vegetables, and livestock for diversified food and income

- Farmer training and improved management nearly doubled fish harvests while boosting climate resilience

- The “One Family One Pond” model strengthens food security and adaptation for households across Cambodia

In Cambodia’s rice-growing regions, small ponds dug beside rice fields can change everything. By capturing and storing water, providing refuge for fish and supplying irrigation for vegetables, they can turn a single harvest into a year-round source of food and income. For farming families, this can mean more meals on the table, less risk from droughts, and a stronger defense against the impacts of climate change.

Cambodia has more than 2 million hectares of rice fields covering both lowland floodplain rice and upland rice systems. Most rice production takes place in the fertile floodplains around the Mekong delta and Tonle Sap Basin, where rice fields also provide habitats and food sources for fish, yet much of this potential remains untapped. Rice-field ponds are small water bodies, dug within or near rice fields to store water.

Rice-field ponds play an important dual role. During the rainy season, they act as water-harvesting and refuge areas for fish especially during dry spells or when pesticides are used in rice fields, and as a pest control agent for rice through the integrated pest management (IPM) role played by aquatic animals. They also allow farmers to link fish, rice, vegetables, and even livestock into one integrated farming system. By doing so, farmers can diversify production, improve nutrition, and strengthen their resilience against climate change. After rice harvest, the fish in the pond provide households with both food and income. Previous studies show that one third of farming households own rice-field ponds, with an average annual yield of around 40 kilograms of fish. These fish may come from the surrounding areas by themselves in the wet season or be collected from the wild and raised in ponds by the owner.

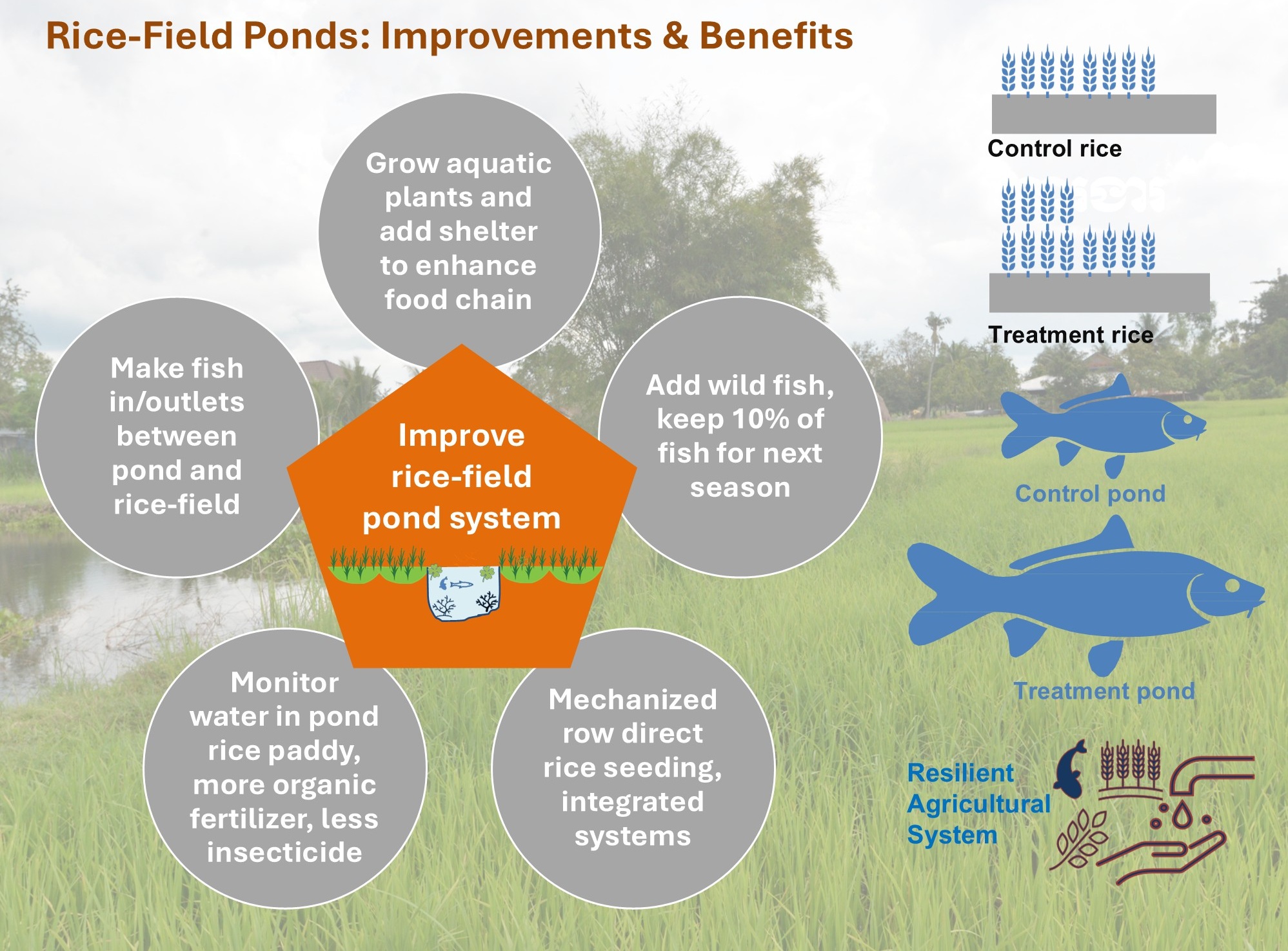

Through training supported by WorldFish and partners, farmers are learning how to make rice-field ponds more productive and climate-resilient.

“Through the training, I realized the importance of having a pond, which can generate up to four times more value than rice, even when rice is grown three cycles a year. I also learned how to improve the rice-field pond system and I am committed to improving my practices so I can increase production and strengthen the rice-field ecosystem.” Mrs. So Moun, Farmer in Kampong Sleng Village.

Lessons from Research and Innovation

Research and experience from the past CGIAR Initiative in Takeo and Prey Veng Provinces show the benefits of improved management:

- 67% higher fish production and greater profits for farmers.

- Improved pond–rice field connectivity, supporting fish migration, biodiversity, and resilience to rainfall variability.

- Two crop cycles and diversified farm products, giving households more stability during droughts.

Integrated Farming in Practice

While rice-field ponds offer great potential, farmers also face several challenges:

- Water shortages in the dry season. Addressed by making the pond deeper thereby improving water storage and improving pond connectivity with the surrounding area. These practices also help maintain broodfish for natural replenishment in the following year.

- Limited feed in the dry season. When ponds are cut off from rice fields, natural food becomes scarce and fish rely only on what is available inside the pond. Farmers can improve the pond’s ecosystem to produce more natural feed and supplement with affordable options like termites, insects trapped with light at night, black soldier fly larvae, or low-cost commercial feed to keep fish growing.

- Competition with intensive rice production. High demand for water and priority given to rice monoculture often reduce attention to integration. Promoting better water management can balance needs and maximize overall productivity (fish, vegetables, and livestock). Having a mix of crops and animals also reduces the risk of theft, since farmers visit the pond or field more often to tend different activities.

- Chemical pesticide use in intensive rice systems. Excessive pesticide application can harm fish and aquatic biodiversity. Encouraging IPM, reducing chemical inputs, and promoting biological pest control through fish and natural predators can protect both rice and pond ecosystems.

- Knowledge gaps in pond management. Training, farmer-to-farmer learning, and demonstration sites help farmers see practical techniques in action. These are followed by field days, which expand adoption across communities by allowing more households to observe results and exchange experiences. This participatory approach ensures that practices remain technically sound, locally relevant, and scalable across diverse contexts.

To demonstrate this nature-based solution, WorldFish and partners under the CGIAR Multifunctional Landscapes (MFL) Initiative have worked with households around Boeng Snae in Prey Veng province, to demonstrate integrated rice-field pond systems to enhance production. Farmers improved inlets and outlets, managed aquatic plants, and installed shelters for fish. They stocked species such as wild snakehead, provided supplementary feed when needed, and retained broodfish after harvest for natural replenishment. Vegetables were cultivated on pond banks or nearby land using pond water for irrigation, while rice continues to be grown with fewer chemical inputs.

“Integrated rice-field ponds contribute to both the local government and the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries’ priority of reducing production costs by optimizing the use of resources already available within the community.” Mr. Prum Sophat, Chief of the District Agriculture Office in Baphnom.

The goals of promoting rice-field pond systems are to: Raise awareness of their benefits; introduce methods to improve productivity and encourage good practices to increase fish harvests.

Key improvements include stronger pond structures, better water management, and connectivity with rice fields. Farmers can classify fish species based on feeding behavior and provide both natural feed (plankton, insects) and supplementary feed (grain-based or homemade). Retaining broodfish after harvest helps sustain fish stocks for the next season.

Benefits for Families, Communities, and Landscapes

By adopting integrated pond systems, farming households can achieve:

- Higher yields of fish, rice, and vegetables.

- Conservation of aquatic biodiversity and wetland organisms.

- Natural pest control and reduced need for pesticides.

- Fertilization of soil through fish waste, reducing chemical fertilizer use.

- More sustainable mixed farming systems and greater resilience to climate shocks.

- Stronger connections between households, ecosystems, and landscapes, ensuring benefits beyond individual farmers.

This “One Family, One Pond” model promotes community-based water management, reduces reliance on external resources, and supports adaptation to climate change. It is recognized in UNFCCC Nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and Cambodia’s Third Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC 3.0) (Adaptation Measure #9) as a promising pathway for climate-resilient pond-based fish production and rice-field ecosystems.

Integrated rice-field pond systems show that farming in Cambodia can be productive, sustainable, and climate-smart which will benefit around almost a million households in Cambodia. More than just fish or rice, they represent a holistic living landscape approach to rural development, where food security, biodiversity, and resilience grow together.