In December 2025, we travelled to Egypt to hold a WorldFish Board meeting and to renew something deeply meaningful: a 25-year extension of our hosting agreement with the Government of Egypt. It was a moment of continuity and trust—one that links our future to a country where aquatic food systems have shaped civilisation itself.

During that visit, we found a moment to visit the Grand Egyptian Museum.

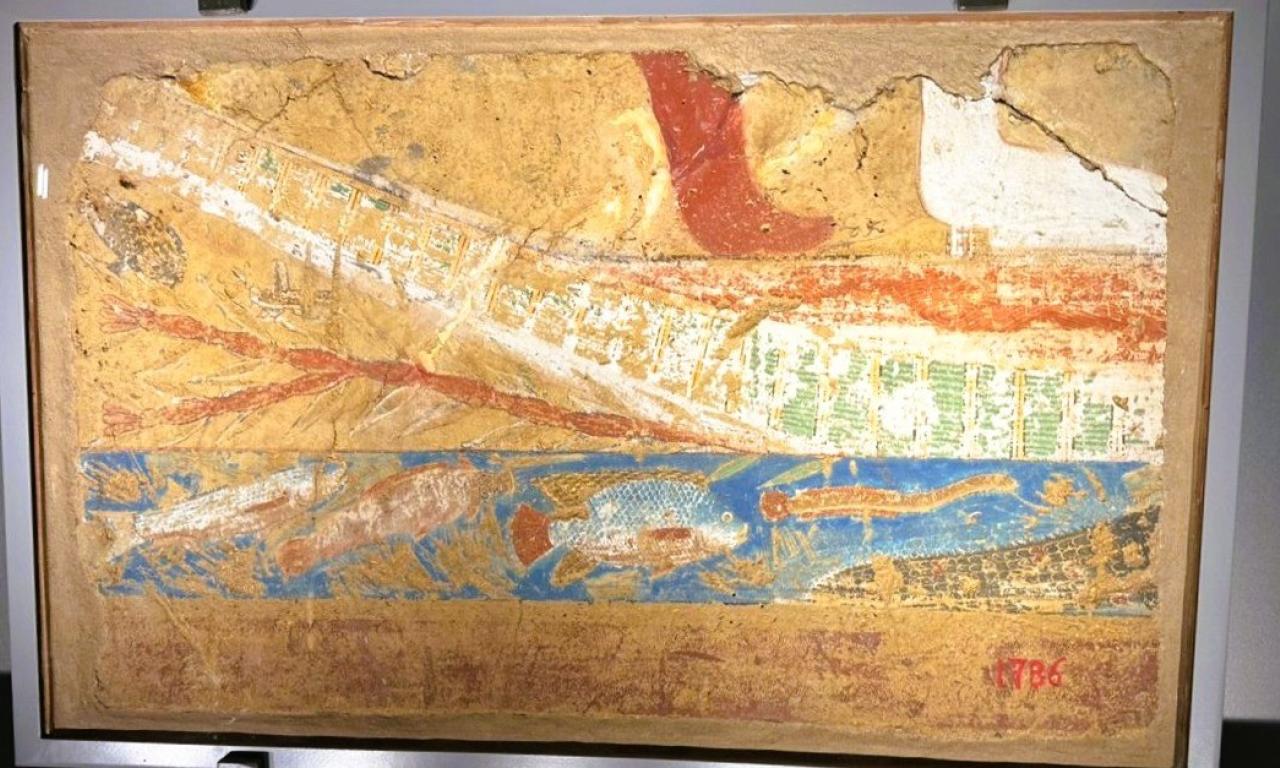

Among statues of kings and queens, monumental temples, and treasures that speak of power and permanence, I came across something unexpectedly simple: fragments of painted walls. Scenes of the Nile. Reeds. Flowing water. And fish.

At first glance, they are unassuming - just fish swimming in a painted river. But the longer I stood there, the harder it became to look away. These paintings are more than four thousand years old, yet the fish felt strangely familiar.

Because they were. They were tilapia, carp, and catfish.

A Moment of Recognition

Those fish on the wall are the same fish that sit at the heart of WorldFish’s work today. The same species that millions of families across Africa and Asia still depend on for food, income, and nutrition.

This was not coincidence. Ancient Egyptians were careful observers of life. They painted what mattered. These fish fed households, sustained communities, and returned year after year with the floodwaters of the Nile. They represented life continuing, even in a harsh and unpredictable environment.

In a way, these paintings are some of the earliest “food system maps” we have - quietly recording how people and nature learned to live together.

What Hasn’t Changed? And What Has?

Fast forward a few thousand years, and the challenges look different on the surface. Climate change. Population growth. Pressure on land and water. Fragile livelihoods.

Yet the foundation remains remarkably familiar.

At WorldFish, we focus our genetic improvement work on tilapia, carp, and (and hopefully soon) catfish because they are still the species best suited to feed people - especially those living on the frontlines of climate and economic uncertainty.

Tilapia grow quickly, convert feed efficiently, and provide affordable protein. Carp underpin some of the most efficient food systems in the world. Catfish survive where other species cannot, thriving in low-oxygen waters and tough conditions.

What ancient communities understood through lived experience, we now support through science: these fish endure because they are resilient, adaptable, and accessible.

Science as Stewardship

Genetic improvement is sometimes misunderstood as something purely technical. But at its core, it is about care.

It is about helping fish farmers produce more food without damaging ecosystems. About making sure nutritious fish remain affordable for families. About supporting women and small-scale producers who depend on aquaculture to build secure livelihoods.

In many ways, our work is less about changing fish and more about honouring their role in human history - while making sure they can continue to play that role in a changing world.

Lessons From a Painted River

Standing in the Grand Egyptian Museum, I was reminded that food systems are not modern inventions. They are long conversations between people and nature, carried across generations.

The fish painted on those ancient walls tell a quiet story of continuity. They remind us that progress does not always mean replacing the old with the new. Sometimes, it means understanding why something has lasted, and helping it endure.

Tilapia, carp, and catfish have fed people for thousands of years. With the right science, care, and partnership, they can continue to do so for thousands more.

Sometimes, the future of food is already swimming in our past.