Parties to the Paris Agreement, the landmark treaty signed by nearly 200 countries to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius by the end of this century, can now reference new guidelines for strengthening their national climate strategies. Released on September 25 at Climate Week NYC, the guidelines include targets for emissions reduction, adaptation strategies, and policy interventions to ensure fisheries and aquaculture, or blue foods, advance climate action.

“We want to remind Parties to the Paris Agreement that the incredible diversity of blue food species offers many possibilities for reducing emissions and adapting to climate change,” said contributing author Michelle Tigchelaar, a climate scientist with WorldFish and a fellow at the Stanford Center for Ocean Solutions who led the report’s development.

Prepared by researchers from the Stanford Center for Ocean Solutions, WorldFish, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Beijer Institute of Ecological Economics, CARE, and the Environmental Defense Fund, the guidelines illustrate how blue foods can support other sustainable development goals, like improved food security and livelihoods, in addition to climate action.

For example, FAO and the governments of Angola, Honduras, and Peru have developed national strategies that incorporate local fish products into school meal programs. In Peru, the harvesting and processing of anchoveta, a small baitfish caught just off the coast, produces one of the lowest carbon footprints of all wild capture species. Anchovies are also packed with nutrients, thereby supporting student health, local livelihoods, and the consumption of low-carbon blue foods all at the same time.

School meal programs illustrate a diet intervention, one of five intervention areas identified in the report: consumption and diets, capture fisheries production, aquaculture production, supply chains, and blue carbon habitats, which are coastal ecosystems like mangroves that sequester carbon.

“We hope that government decision-makers consider how these policy options and real-world examples can support other areas of climate planning, such as energy, nutrition, and economic development,” said contributing author Laura Anderson, Engagement Project Manager at the Stanford Center for Ocean Solutions.

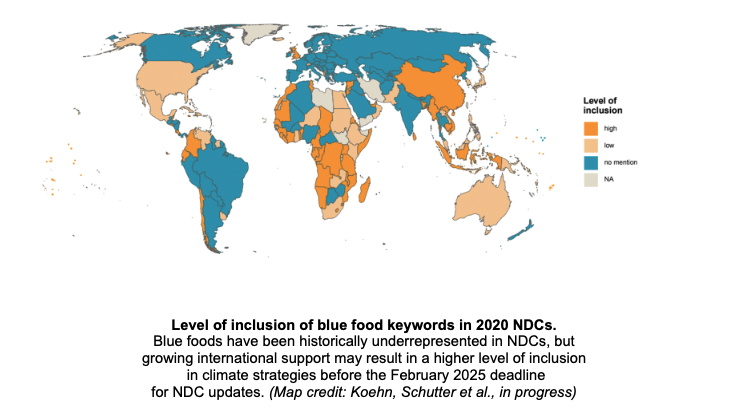

Parties to the Paris Agreement commit to creating national climate strategies, called nationally determined contributions (NDCs), that outline their plan for reducing emissions. Countries submit updated NDCs every five years to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the international forum for climate negotiations that produced the Paris Agreement in 2015. Updated NDCs are due in February of 2025.

“The Parties to the Paris Agreement have only just begun to recognize the central importance of food systems to their goals for climate mitigation and adaptation,” said Jim Leape, co-director of the Stanford Center for Ocean Solutions and the William and Eva Price Senior Fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment. “These guidelines will help them capitalize on the roles blue foods can play in achieving those goals.”

Read the guidelines and join a webinar this October to explore concrete policy options and regional case studies.